IN WHICH WE LEARN THE SECRET HISTORY OF POOH AND, DOING SO, ARE NOT QUITE THE SAME AGAIN

“Where are we going?” said Pooh, hurrying after him, and wondering whether it was to be an Explore or a What-shall-I-do-about-you-know-what.

“Nowhere,” said Christopher Robin.

So they began going there . . .

There are in total 20 Winnie-the-Pooh stories, two collections of ten. The first collection is called Winnie-the-Pooh and the second The House at Pooh Corner. The very last story of all, the one at the end of The House at Pooh Corner, is called In Which Christopher Robin and Pooh Come to an Enchanted Place, and We Leave Them There. It is a masterpiece, a tiny work of genius.

I don’t know how many times I’ve heard the Winnie-the-Pooh stories. My mother first read them to me when I was very small. Later I read them to myself. Later again I read them to my five children. They are a delight to read aloud:

Here is Edward Bear, coming downstairs now, bump, bump, bump, on the back of his head, behind Christopher Robin.

But even from that first line of the very first story, I’m aware how every page turn brings the last story creeping ever closer. And what kid doesn’t beseech just one more Pooh story before sleep? Which makes the Enchanted Place loom closer still. I confess to dreading its approach. I dread its approach because I know I won’t be able to read it without my voice quavering and I break into tears. And as the stories tread and leave the stage one by one, I steel myself against the inevitable. An Enchanted Place is perhaps the saddest story ever written.

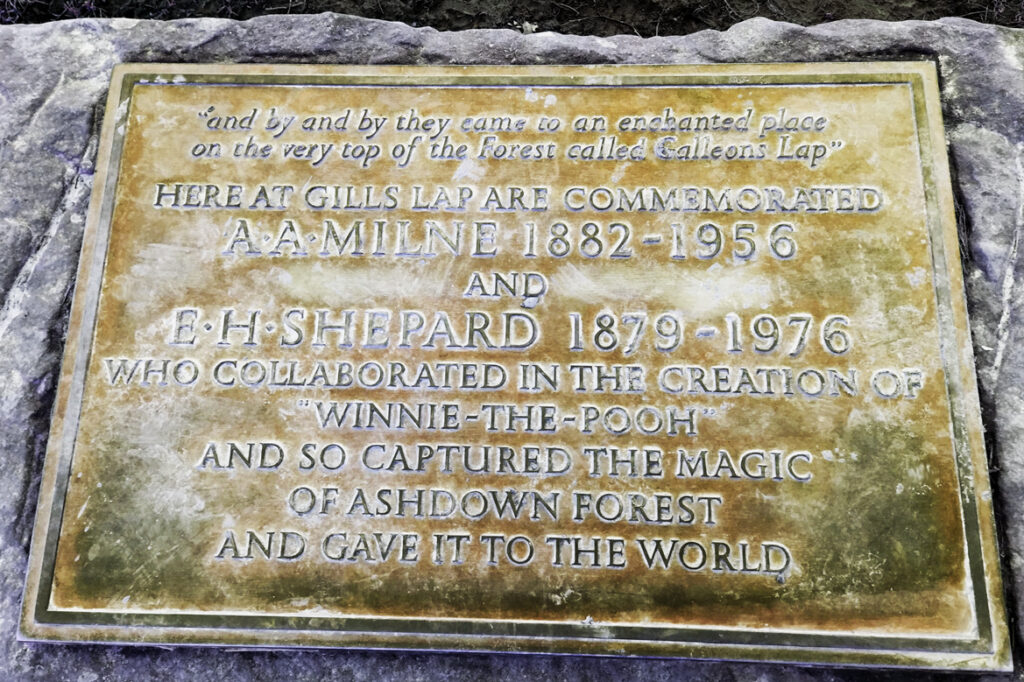

Surprisingly, the place where the story is set is real. It lies along the B2026, Chuck Hatch Road, between the villages of Hartfield and Duddleswell, Sussex, UK. A plaque close by recognises its importance to the Winnie-the-Pooh legacy. There is a car park to park in.

In 1924, Alan Alexander Milne (1882-1956), author of Winnie-the-Pooh, bought Cotchford Farm, a ‘more or less derelict’ farmhouse set on 9 acres near Hartfield. It was to become the family’s weekender. Alan, his wife Daphne and young son Christopher would drive down from London each Saturday morning to the cottage nestling on the border of Ashdown Forest. A A called the sitting room the ‘most lovely room in the whole world’. He smilingly bumped his head on the low beams of its ceiling. It had a big fireplace at the centre and French doors leading to a wide lawn and gurgling stream in the dell.

Alan Milne was a natural writer. ‘The whole art of writing’, he once said, is ‘to know what it would be any good putting.’ And putting what was good he had a knack for. At school in North London, he had H G Wells, later the author of The Time Machine, The Invisible Man and The War of the Worlds, as a teacher. At Cambridge, he wrote and edited the magazine Granta, though his BA (1903) was in mathematics. After graduating, he began contributing humorous verse and articles to Punch magazine, where he eventually became an assistant editor. In 1913, he married Dorothy “Daphne” de Sélincourt. During World War I, Milne joined the Army. He served on the Somme in 1916, caught trench fever and was invalided home. He did some work writing propaganda for MI7, eventually being discharged in 1919. Then, in August 1920, his only child Christopher Robin Milne was born.

For his first birthday, Christopher received a teddy bear from Harrod’s. Like most bears, this bear’s name was Teddy or, more properly, Edward Bear. After the Milnes bought Cotchford, for weekends, Easter and summer holidays, Edward Bear made the hour and a quarter trip in the blue Fiat car from London to Hartfield. Christopher’s nurse—Olive Rand, whom he called Nou, went too. The world would come to know Nou as Alice, because Alice rhymed with ‘palace’:

They’re changing guard at Buckingham Palace—Christopher Robin went down with Alice.

The tulip bulbs that Daphne planted at the farm in autumn 1924 came excitingly into flower the following May. She fell in love with the Cotchford garden, enjoying its solitude. A A styled himself the ‘under-gardener’. ‘That a nasturtium seed to take any further interest in life is the most optimistic thing that happens in the world,’ he decided. He took charge of making a putting green to practise his golf and a pond to capture water from a spring. Billy Moon—Christopher Robin by his pet name—spent the days playing and having fun.

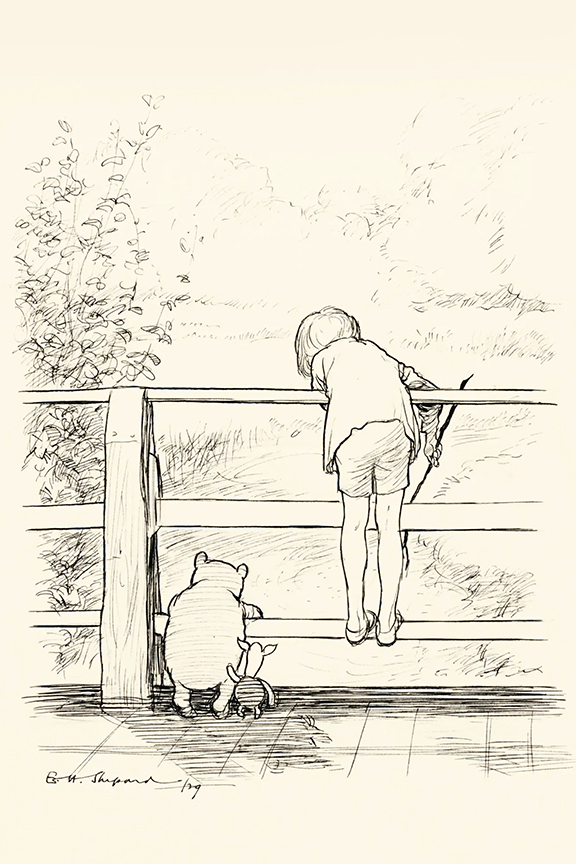

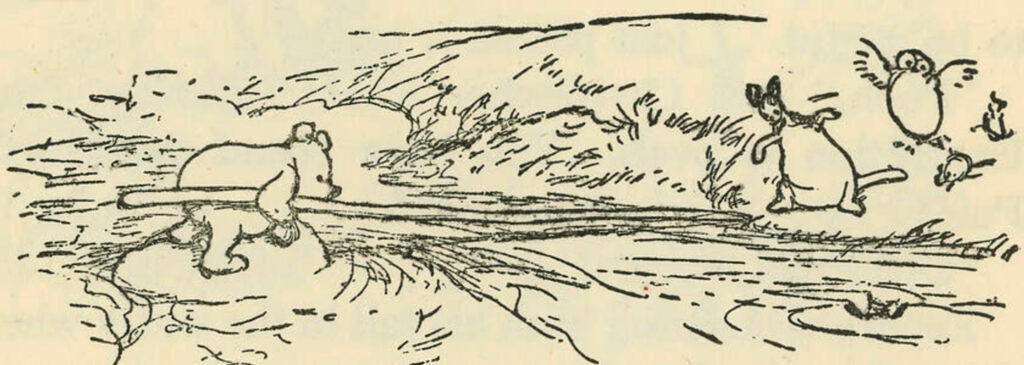

Beyond the stream in the dell lay a meadow, and at the other side of the meadow a small river, a tributary of the Medway, flowed lazily. ‘It was just the right width: too wide to jump, but where a kindly tree reached out a branch to another kindly tree on the opposite shore, it was possible to swing yourself over. It was just the right depth: too deep to paddle across but often shallow enough to paddle in and places deep enough to swim.’ Upstream, to the south-west, a bridge spanned the river—one day to be christened ‘Poohsticks Bridge’ because of the game that was invented on it.

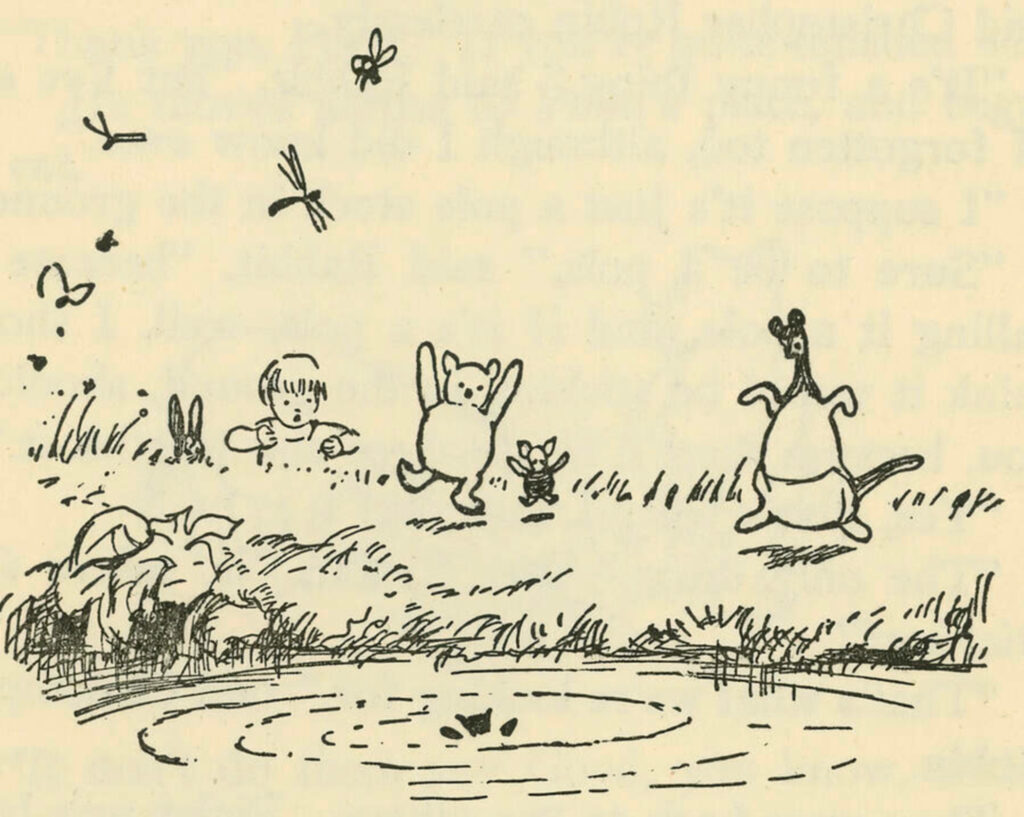

One fine day, along this same river, Christopher Robin’s Expotition to the North Pole will journey, and Roo will fall into the cold waters, squeaking proudly: ‘Look at me swimming!’ And Winnie-the Pooh will rescue him. But that’s all still to come.

In the beginning there were just three animals: a teddy bear named Edward, a donkey with a droopy neck named Eeyore, and a piglet named Piglet, Edward’s best friend. Then the bear changed his name.

‘Winnie’ was short for Winnipeg, an orphaned American black bear cub whom Christopher Robin loved visiting at London Zoo, brought to England and donated by a Canadian soldier fighting in World War 1. Alan Milne, interviewed in 1926, told Enid Blyton: ‘The bear hugged Christopher Robin and they had a glorious time together, rolling about and pulling ears and all sorts of things.’

The name ‘Pooh’ had once belonged to a swan whom Christopher Robin met briefly near Arundel, Sussex in 1921. Pooh ‘is a very fine name for a swan, because if you call him and he doesn’t come (which is a thing swans are good at), then you can pretend that you were just saying ‘Pooh!’ to show how little you wanted him . . . We took the name with us, as we didn’t think the swan would want it anymore.’

The very first Winnie-the-Pooh story appeared in print on Christmas Eve 1925 in the London Evening News. The story was titled The Wrong Sort of Bees. Asked for a children’s story, Alan Milne struggled to come up with something. ‘Write down any one of those bedtime stories,’ Daphne told him.

‘They’re not really stories,’ Alan said.

‘Surely there must be one?’ Daphne persisted. And there was. Alan suddenly remembered a story. A story that was real. A story about Christopher Robin’s bear. He started writing:

This is Big Bear, coming downstairs now, bump-bump on the back of his head, behind Christopher Robin. It is, as far as he knows, the only way of coming downstairs, but sometimes he feels that there really is another way, if only he could stop bumping for a moment and think of it. And then he feels that perhaps there isn’t. Anyhow, here he is at the bottom, and ready to be introduced to you. Winnie-the-pooh.

Yes, Pooh began literary life with a small p. The headline for his debut stretched the whole width of the Evening News’ front page, eclipsing a great storm that was sweeping across Derbyshire:

The Wrong Sort of Bees was not illustrated by Ernest H. Shepard (1879-1976), the artist whose drawings would become synonymous with both Winnie-the-Pooh and Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows. But Shepard had already ‘decorated’ Alan Milne’s book of poems When We Were Very Young in 1924. Now Milne asked if he would draw pictures for a book of ten stories about a teddy bear. He straightaway sent Shepard four of the ten ‘so you can get an idea at once . . . I want you to see Billy’s Bear. He has such a nice expression.’ Alan desperately wanted Ernest Shepard to meet the toys. Alan and Daphne, on a hunt together in Harrods, searching for additions to Pooh, Piglet and Eeyore, had discovered Kanga and Roo. Meanwhile, Alan had been inventing the characters Rabbit and Owl.

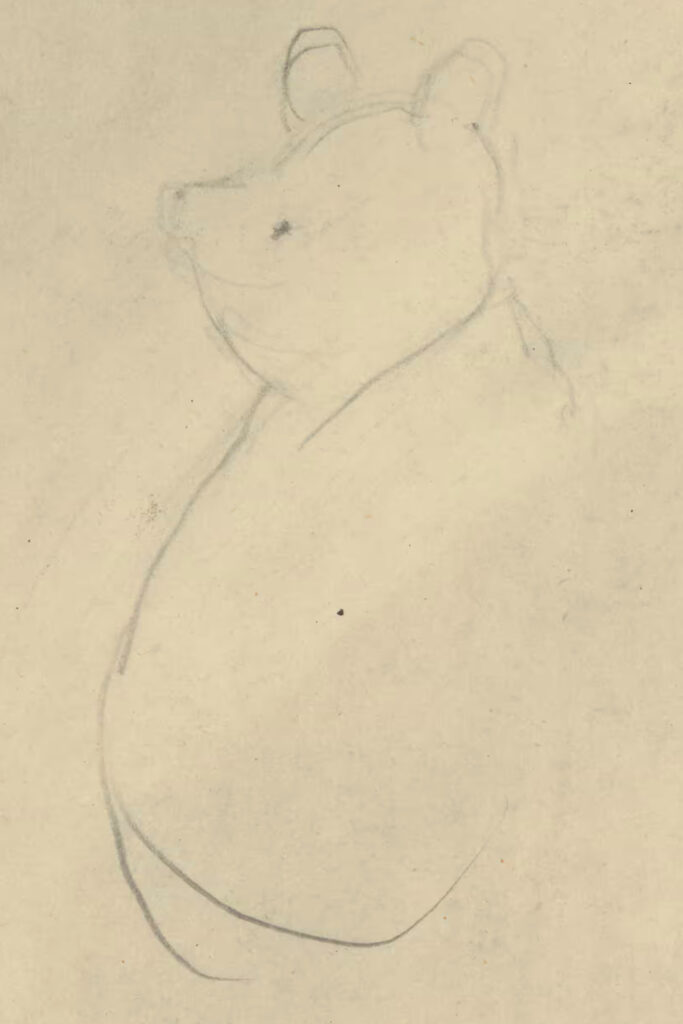

However, when Shepard finally came to visit, he thought Christopher Robin’s teddy bear too gruff-looking to use as a model for Pooh. Instead he wanted to use his own son Graham’s bear, Growler. Growler, who was tubby and impressive, had already made a public appearance in When We Were Very Young. In fact, it is Growler whom we’ve come to know and love as Winnie-the-Pooh, not the bear who today lives in a climate controlled glass case in the New York Public Library’s Children’s Center.

Only a tattered photo of Growler, taken around 1913, survives. The bear, quiet and dignified, sits very Pooh-like on the floor behind Graham Shepard and his sister, Mary. Both children grew up to become well-known illustrators in their own right. Like her father, Mary lived into her nineties. But tragically, Graham Shepard died when the ship he was serving aboard during World War 2 was torpedoed. His daughter Minette inherited Growler. But Growler also is no more, sadly the victim of an unfortunate incident involving a neighbour’s dog.

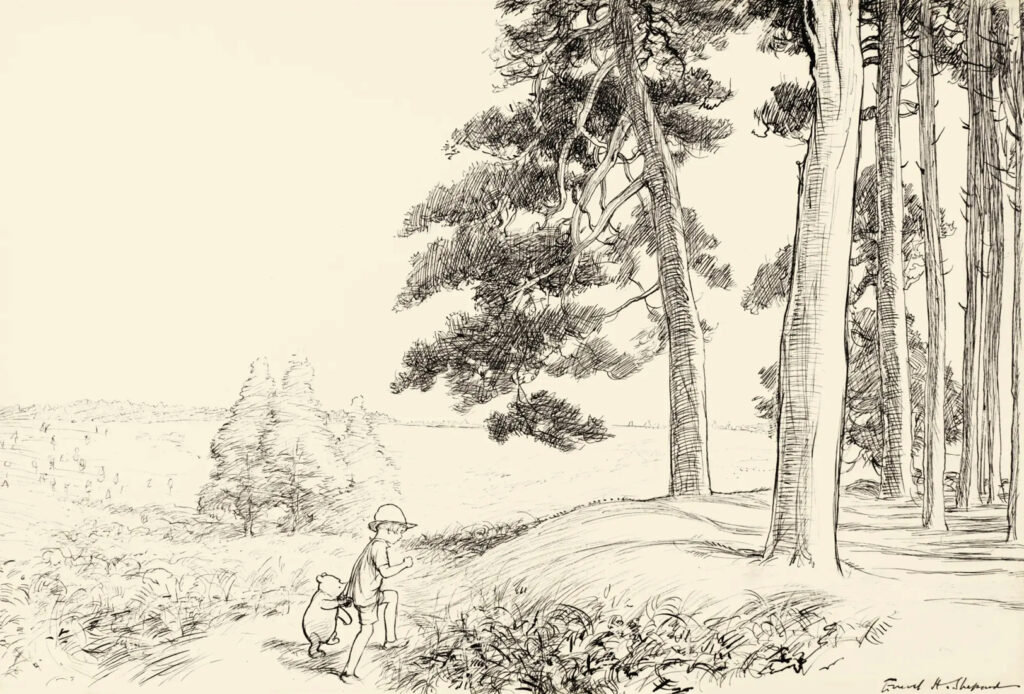

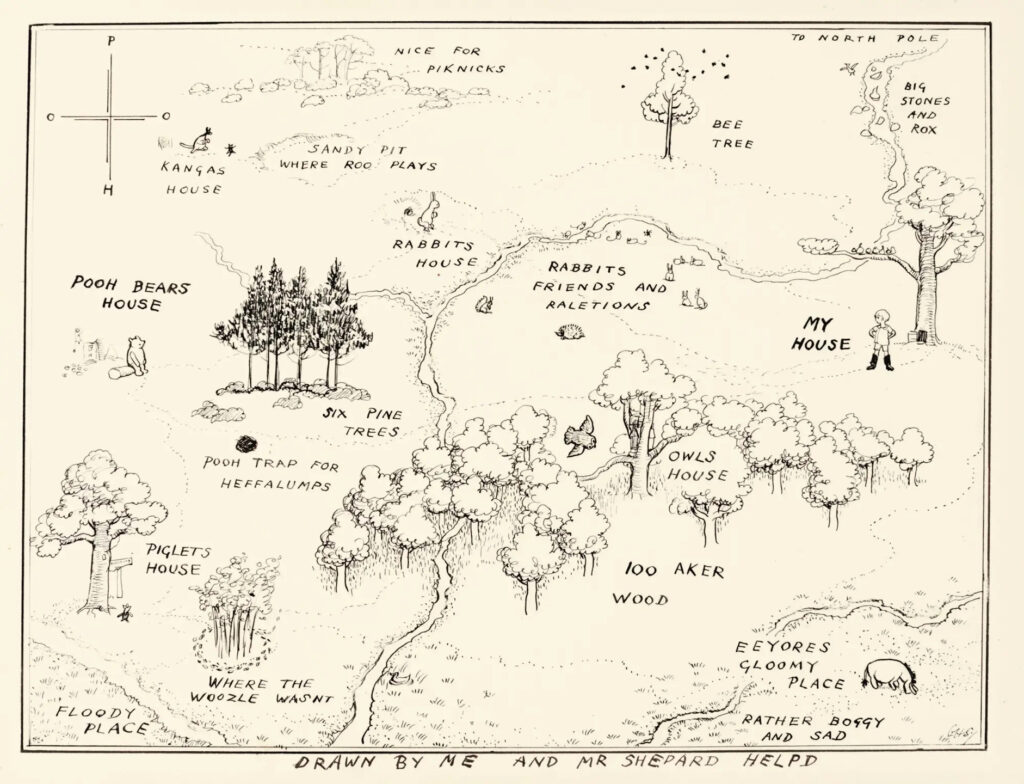

Ernest Shepard believed that his own son’s legs were more sturdy than Christopher Robin’s. ‘Otherwise,’ he wrote, ‘I was a stickler for accuracy. All the illustrations of Christopher Robin, Pooh and Piglet and the other animals were drawn where Milne had visualised them—usually in Ashdown Forest.’

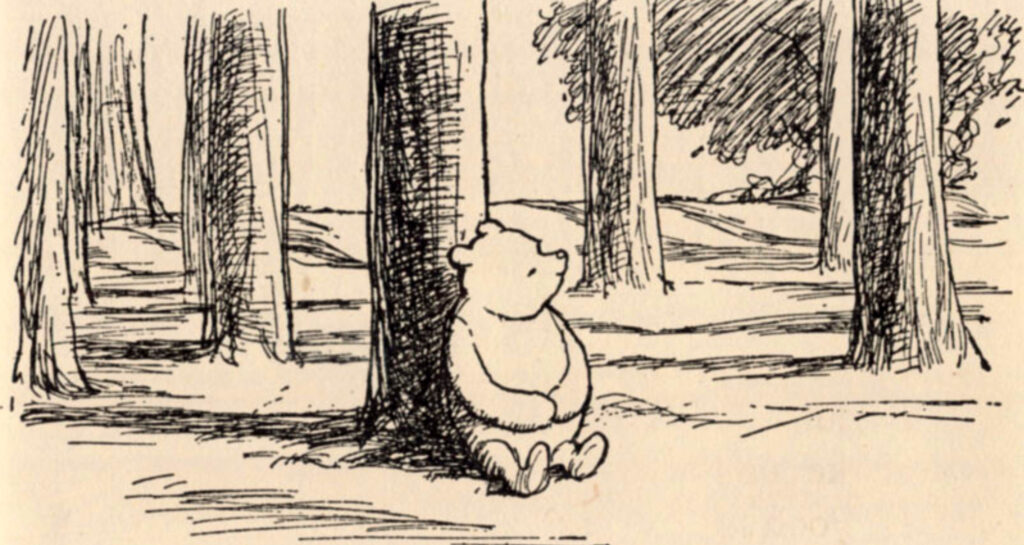

And herein lies one secret of the Winnie-the-Pooh stories. Inside the house at Cotchford, Pooh is a stuffed toy, dragged and pulled. But outside, under trees and clouds, over snow and heather, stepping stones and meadow grass, beside a tinkling stream or through a copse, hearing the cuckoo and smelling the sweet May air, Pooh is alive. He’s an adventurer, a wandering philosopher, a poet.

On previous meetings, Ernest Shepard had felt Alan Milne was difficult to get to know: ‘I always had to start again at the beginning with Milne every time I met him, I think he retired into himself—very often and for long periods.’ But when Shepard took his family down to Cotchford he found a quite different Alan Milne, open and full of enthusiasm. Joyfully pointing to things in the landscape, Alan was eager to show Shepard, who was never without a pencil, all the places where the story events actually happened. Mary Shepard remembered Christopher’s happiness playing make-believe games with her brother Graham. Graham was in his late teens, and Christopher seemed surprised that anyone older would play other than ball games—’dog games’ as he called the ones his father mostly played.

Two minds came together on that springtime family walk across the forest. If there’s a genesis to the Pooh books, this is it. After a stop at Poohsticks Bridge, everyone returned happily up the lane in time for tea at Cotchford.

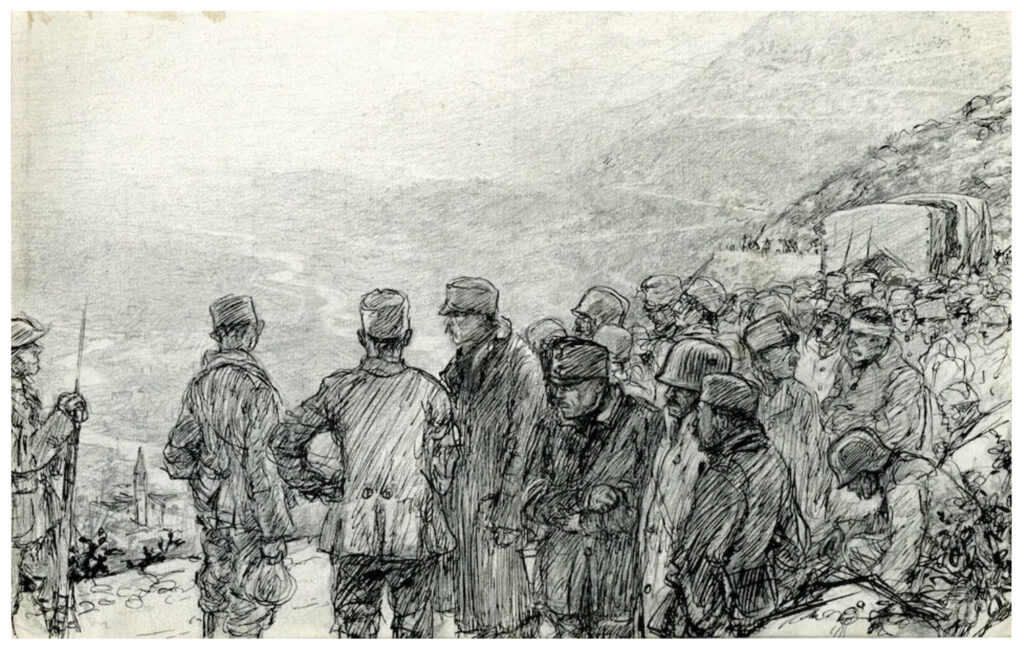

Nearly a decade before this, both Milne and Shepard had served in World War 1, and both had fought at the 1916 Battle of the Somme, which cost the lives of 300,000 men and came to symbolise the futility and senselessness of war. Alan Milne called the Somme ‘a degradation which would soil the beasts, a lunacy which would shame the madhouse.’ The battle affected the lives of many, including the author of The Lord of the Rings, J R R Tolkien, and the poet Robert Graves. Ernest Shepard went on to serve at Arras, Ypres and Passchendaele, but on the first day of the Somme offensive, his older brother Cyril was killed. For his bravery at Arras, Ernest Shepard received the Military Cross. But once demobilised, everything connected to the war, his medal and the countless drawings he had made in the trenches and on the battlefield, he packed away and never got out again for the rest of his life.

As for Alan Milne, war changed him forever. If Ernest Shepard found him hard to get to know and withdrawn, the horrors of the Somme had played their part. When Milne first set out for the Front in July 1916, he travelled to France with a boy whose elder brother had already been killed. Desperate to protect the life of her one remaining son, the boy’s mother had given him

an under-garment of chain-mail, such as had been worn in the Middle Ages to guard against unfriendly daggers, and was now sold to over-loving mothers as likely to turn a bayonet-thrust or keep off a stray fragment of shell; as, I suppose, it might have done. He was much embarrassed by this parting gift, and though, true to his promise, he was taking it to France with him, he did not know whether he ought to wear it. I suppose that, being fresh from school, he felt it to be ‘unsporting’; something not quite done; perhaps, even, a little cowardly. His young mind was torn between his promise to his mother and his hatred of the unusual. He asked my advice: charmingly, ingenuously, pathetically. I told him to wear it; and to tell his mother that he was wearing it; and to tell her how safe it made him feel, and how certain of coming back to her. I do not know whether he took my advice . . . Anyway it didn’t matter; for on the evening when we first came within reach of the battle-zone, just as he was settling down to his tea, a crump came over and blew him to pieces . . .

No war in history had been like this, and no chain-mail could defy its ferocity. After the world had done blowing itself to smithereens, a terrible disillusionment and feeling of loss took hold, as if the smoke and mustard gas had permanently smudged out the sun. What faith could be had in a civilisation able to spawn such horror and carnage? It questioned sanity itself.

Like Edward Elgar, whose 1919 Cello Concerto broods on a melancholy so deep, try as it might, it can find no way back to the light, Alan Milne sought refuge in the tranquility of the English countryside. But even here, the trauma of war intruded:

Oh, I’m tired of the noise and the turmoil of battle

I’m even upset by the lowing of cattle,

And the clang of the bluebells is death to my liver,

And the roar of the dandelion gives me a shiver.

On one of their many trips to London Zoo, Milne remembered Christopher Robin ‘took me into the Insect House, and at the sight of some of the monstrous inmates I had to leave his hand and hurry back into the fresh air. I could imagine a spider or a millipede so horrible that in its presence I should die of disgust. It seems impossible to me now that any sensitive man could live through another war.’

Chapter X of The House at Pooh Corner opens:

Christopher Robin was going away. Nobody knew why he was going; nobody knew where he was going; indeed, nobody even knew why he knew that Christopher Robin was going away. But somehow or other everybody in the Forest felt that it was happening at last.

All the animals come to Christopher Robin’s house to say goodbye. Then Christopher Robin and Pooh go off one last time to share that magic feeling of nowhere to go:

‘What do you like doing best in the world, Pooh?’

‘Well,’ said Pooh, ‘what I like best in the whole world is Me and Piglet going to see You, and You saying “What about a little something?” and Me saying, “Well, I shouldn’t mind a little something, should you, Piglet,” and it being a hummy sort of day outside, and birds singing.’

‘I like that too,’ said Christopher Robin, ‘but what I like doing best is Nothing.’

‘How do you do Nothing?’ asked Pooh, after he had wondered for a long time.

‘Well, it’s when people call out at you just as you’re going off to do it, What are you going to do, Christopher Robin, and you say, Oh, nothing, and then you go and do it.’

‘Oh, I see,’ said Pooh.

‘This is a nothing sort of thing that we’re doing now.’

‘Oh, I see,’ said Pooh again.

‘It means just going along, listening to all the things you can’t hear, and not bothering.’

‘Oh!’ said Pooh.

And so we arrive at the Enchanted Place, ‘Galleon’s Lap, which is sixty-something trees in a circle; and Christopher Robin knew that it was enchanted because nobody had ever been able to count whether it was sixty-three or sixty-four, not even when he tied a piece of string round each tree after he had counted it.’

Our visit unlocks a deeper secret behind Winnie-the-Pooh, woven as much into the fabric of Alan Milne’s stories as it is into Edward Elgar’s Cello Concerto. Look across the quiet countryside, ‘the world spread out until it reached the sky’. Don’t use the brain that tells you things. Use the brain of Pooh Bear the Faithful Knight. Be content for a moment with mystery, and a certain marvellous ability not to understand anything. The secret then lies all around. It’s everywhere and always—the world just being what it is. And you are being it too. The raw fact of its being is incredible. Agonisingly, dumbfoundingly so, especially for Bears of Very Little Brain. It’s no wonder we want to push it away, dress it up in funny names, cut it into chewable pieces, make it into something we can grasp and control. Into one simple sentence, Alan Milne compresses the poignancy of the human struggle—our obsessions about hierarchy, territory, knowledge, heroism, all the silliness, vanity and pomp:

People called Kings and Queens and something called Factors, and a place called Europe, and an island in the middle of the sea where no ships came, and how you make a Suction Pump (if you want to), and when Knights were Knighted, and what comes from Brazil.

All of it pointless, a word originally referring to the sharp end of a sword. Meaningless. Why? Because war has systematically eroded the meaning of everything, till all is aglow with strangeness and unreality. Tragically, unthinkably, insanely, blinded by self-importance, sometimes it takes the horror of war to truly open our eyes.

‘Is it a very Grand thing to be an Afternoon, what you said?’

‘A what?’ said Christopher Robin lazily, as he listened to something else.

‘On a horse,’ explained Pooh.

‘A Knight?’

‘Oh, was that it?’ said Pooh. ‘I thought it was a—Is it as Grand as a King and Factors and all the other things you said?’

‘Well, it’s not as grand as a King,’ said Christopher Robin, and then, as Pooh seemed disappointed, he added quickly, ‘but it’s grander than Factors.’

‘Could a Bear be one?’

‘Of course he could!’ said Christopher Robin. ‘I’ll make you one.’

And he took a stick and touched Pooh on the shoulder, and said, ‘Rise, Sir Pooh de Bear, most faithful of all my Knights.‘

Pooh knows he’s not getting it right. He begins to think ‘of all the things Christopher Robin would want to tell him when he came back from wherever he was going to, and how muddling it would be for a Bear of Very Little Brain to try and get them right in his mind. “So, perhaps,” he said sadly to himself, “Christopher Robin won’t tell me any more,” and he wondered if being a Faithful Knight meant that you just went on being faithful without being told things.’

And here is the sad irony. Pooh wants to grow up, like Christopher Robin. He doesn’t want to be the one left behind. But Christopher Robin is betrayed into going to boarding school as surely as Jesus to the cross. Only Pooh remains forever faithful to the glimpse of eternity we commonly call childhood. And only because he has no choice.

At the end of Winnie-the-Pooh he receives a special present:

When Pooh saw what it was, he nearly fell down, he was so pleased. It was a Special Pencil Case. There were pencils in it marked ‘B’ for Bear, and pencils marked ‘HB’ for Helping Bear, and pencils marked ‘BB’ for Brave Bear. There was a knife for sharpening the pencils, and india-rubber for rubbing out anything which you had spelt wrong, and a ruler for ruling lines for the words to walk on, and inches marked on the ruler in case you wanted to know how many inches anything was, and Blue Pencils and Red Pencils and Green Pencils for saying special things in blue and red and green. And all these lovely things were in little pockets of their own in a Special Case which shut with a click when you clicked it.

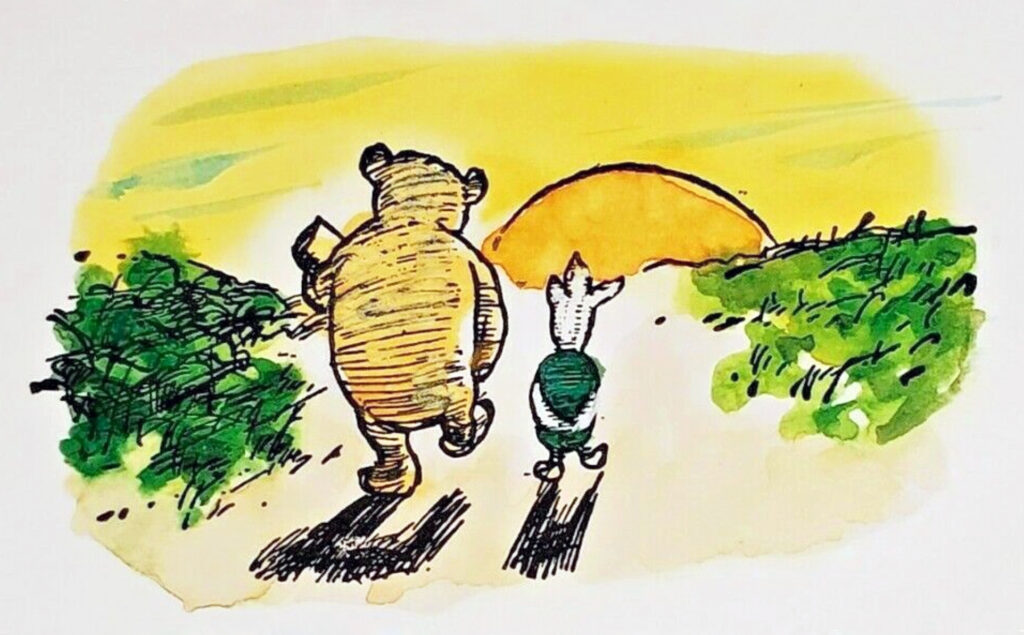

Pooh is the artist, the poet, the Knight of Faith. In the last picture of Winnie-the-Pooh, Pooh and Piglet walk together in the ‘golden evening’, Pooh proudly carrying his tools of Mental Fight: his new pencil case. This picture was one of two A A Milne loved most. He wrote in a little dedication to Ernest Shepard:

When I am gone

Let Shepard decorate my tomb

And put (if there is room)

Two pictures on the stone:

Piglet, from page a hundred and eleven

And Pooh and Piglet walking, (157) . . .

And Peter, thinking that they are my own,

Will welcome me to heaven.