What is needed is just this: aloneness, great inner aloneness. Going into yourself and not meeting anyone for hours—that’s what you have to be able to do. Alone, the way you were alone as a child when grown-ups went around involved in things that must be big and important, because the grown-ups appeared so busy and because you didn’t understand anything of what they were doing.

Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet, Rome, December 23, 1903

A WINTER morning, January 1912. The battlements of a castle, where a solitary man walks to and fro. From time to time, he scans the clear blue waters of the Adriatic Sea. It’s a blue as blue as a poison bottle, and a wild north wind, fresh off the Alps, is whipping the blue into little silvery peaks, like egg white. The air is fiercely cold, burning the nostrils, making the teeth ache.

The man is 36. He is Bohemian, from Prague, a wandering poet. A restless spirit, always on the move, calling no place home—Rainer Maria Rilke. He has eyes the colour of the water he looks over, and his face is long and pale. Hugging his coat around his narrow shoulders, he seems lost in thought. But he’s not composing poetry. He never does. He waits for poetry to come to him, and he has gone two years hardly writing anything. This morning his thoughts are much more matter-of-fact—a business letter he’s been putting off replying to.

He climbs down the narrow path to the foot of the castle. From here, there’s a drop of two hundred feet to the sea. The howling wind quiets a little between the castle bastions. Musty smells of wintry vegetation mix on the salt sea air.

Rilke stops. He listens. Through the mental clatter of the letter and the sound of the blast, he hears something else entirely—a voice calling:

Wer, wenn ich schriee, hörte mich denn aus der Engel Ordnungen?

Who, if I cried, would hear me among the angelic orders?

‘Was ist das?’ Rilke whispers to himself. ‘Was kommt?’ What is coming?

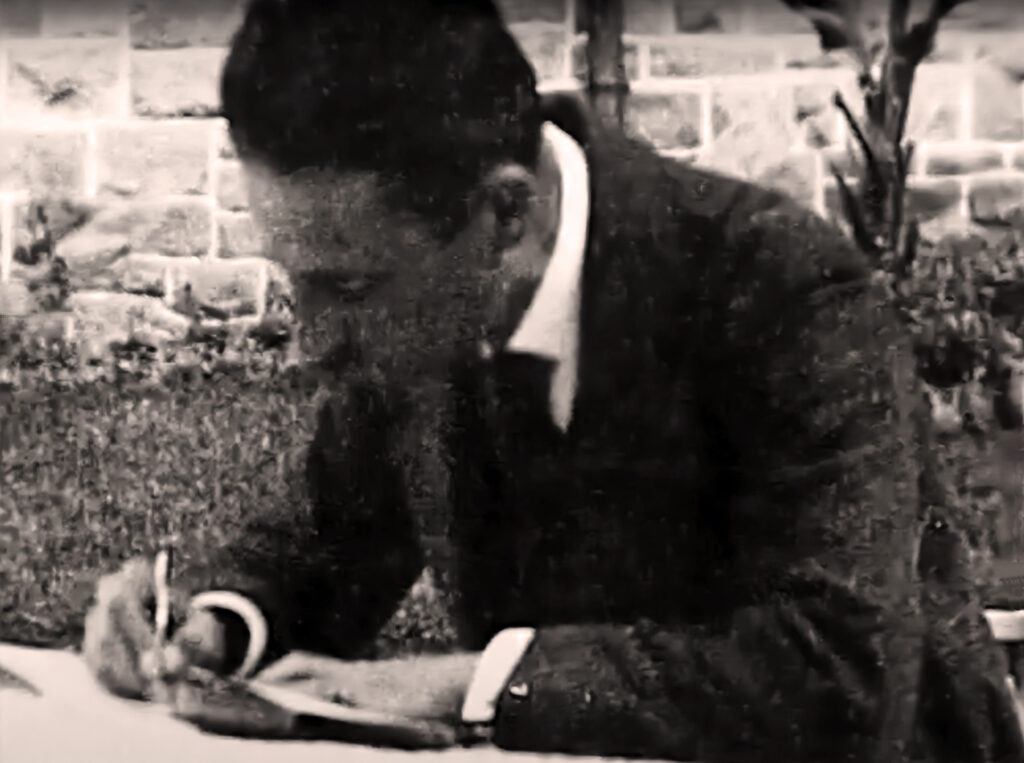

Fingers trembling with cold, he grabs from his pocket the little notebook that waits for just such a moment. Its pages flutter, the wind threatens to snatch them away. The moment mustn’t be lost. Rilke’s sincerity as a poet only lets him write from direct dictation, and he is secretary to an inconstant muse who often forsakes him for months, even years.

Not on this violent, blustery day. He is about to transcribe the first fragments of what will be his greatest work: Duineser Elegien—the Duino Elegies. By evening, the First Elegy will be complete. It is the first of ten, and the poet will have to wait ten years for his muse to finally let him finish the job.

The Duino Elegies are so named after the castle overlooking the Gulf of Trieste where Rilke began writing them. The city of Trieste lies a few miles east. In the nineteenth century, this castle belonged to Czech Prince Alexander von Thurn und Taxis and his wife Princess Marie, whose guest Rilke was in 1911-12. He and the princess, twenty years his senior, were good friends. As autumn in Duino turned to winter, the two spent regular evenings punctually from six in the princess’s drawing room, reading and translating Dante into German. Rainer brought the oil lamp from his room to provide extra light. He hoped translating Dante might encourage his own muse to notice him.

The plan had always been that come mid-December, Marie would rejoin her husband in Bohemia and leave the poet alone at the castle to work. Carlo the old butler and Miss Greenham the English housekeeper would look after him. Rilke, who knew better than anyone the value of solitude, got ready.

‘I shall have to try and climb over the hump of the year here, . . . inside these old walls; outside, the sea, the karst, rain, maybe tomorrow storm: now we shall see what the inner self offers as a counterweight to such prodigious elemental forces. So—unless something quite unexpected turns up—I shall stay here, hold out, keep still, in a sort of curiosity about myself . . . Hearts, like medicine bottles, bear the words “Shake well before taking”, and I’ve been continually shaken up these past years but never taken, so it’s better I should aim now in quietness for clarity and productivity.’

He ordered a standing-desk, because he liked to work standing up. He wandered the gardens. Instinctively he felt that the castle was the right place, ‘towering against the sea, like foothills of human existence, with many of its windows (including my own) looking out to the vast open expanse of ocean, directly into the universe . . .’ He drank no alcohol—he never did. Carlo served his vegetarian meals ‘with the infinite benevolence of a big old dog who allows some puppy to eat out of his bowl . . . At 7, I have a supper worthy of a child, and am ready for bed just after 9, Lord preserve my simplicity.’

Whatever he had enjoyed for supper as a child, Rilke’s childhood was certainly unusual. Till the time he went to school, his mother dressed him as a girl. ‘I was a play thing, like a big doll,’ he wrote. His original first name had been René, though his mother called him her ‘sweet little Sophie’. At eleven, he was sent to military school, accompanied by a nurse. He hated the school, but was forced to stay for five years before running away.

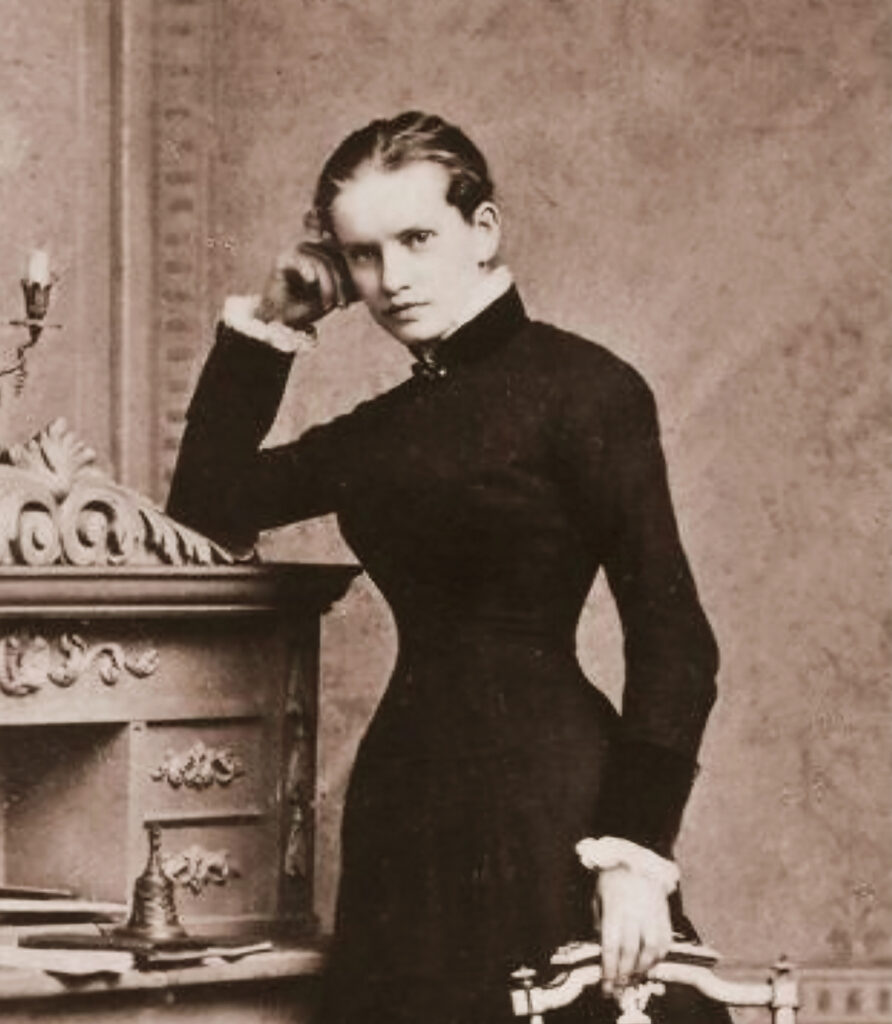

At twenty-one, in Munich, he met Lou Andreas-Salomé, the beautiful 36-year-old Russian-born author, polymath, feminist, friend and confidante to Friedrich Nietzsche, then later to Sigmund Freud. Lou became the world’s first female psychoanalyst.

Every man who met her fell in love with the irresistible Lou. Those who managed to escape the lure of her lovely physical form were quickly seduced by her mind—not surprisingly, because Lou didn’t discriminate between the two. Body and mind for her were one sensuous whole. Neither did she discriminate between rational and irrational, male or female. All such distinctions she felt were unreal. Mind is an illusion, a magic mirror. Narcissus sees a face in the stream and wonders whose it is. Mind comes on board life ‘as a fragile infant climbs into its grandfather’s lap’.

An infatuated Friedrich Nietzsche proposed to Lou three times. She turned him down. Instead she gave in to a stuffy professor of Eastern languages, Friedrich Andreas, who threatened suicide if she didn’t agree to marry him. She did, but only on condition that he allowed her the freedom to lead an ‘independent’ life, meaning that their marriage went unconsummated.

Lou described her relationship with Rilke as being ‘husband and wife even before we became friends, not by choice, but by this unfathomable marriage . . . like brother and sister, but from primeval times before incest became a sacrilege.’

Instead of the feminine-sounding René, Lou called him Rainer, ‘plain, fine, German’. His handwriting was all but illegible. Lou made it elegant. She was the springboard for his inspiration. Rilke swam out to very deep waters. But Louise von Salomé was the shore he never let out of his sight.

Together with Lou, Rilke made two visits to Russia. On the second, he met Tolstoy. Returning to Germany, he joined a colony of artists in the town of Worpsvede near Bremen. Another member of the colony was the sculptor Clara Westhoff, whom Rilke would marry.

They had a baby. There was little money. Clara went to stay in Holland. Rilke went to Paris. Here he came in contact with the next great influence on his poetry, Auguste Rodin, whose student Clara had been. For four years from 1902, Rilke was Rodin’s assistant and lived on the sculptor’s country estate outside Paris. ‘Travailler, toujours travailler,’ the 61-year-old Rodin advised his young protégé poet. ‘Work, always work. Work and be patient.’

All very well. Rodin’s work involved a hammer which he swung with energetic delight. Rilke wanted to sculpt words the way Rodin sculpted clay. He wanted a poetry of ‘hand-work’, a real poetry, a poetry of things. But where to begin? Patience he had in spades. But for now, patience was all he had:

There’s no measuring with time, there is no year, and ten years is nothing. Being an artist means not counting and calculating. Ripen like the tree that doesn’t force its sap and stands trustingly in the spring storms, never fearing that summer won’t come. It will come. But only to the patient, to those who wait as if eternity lay before them, carefree, quiet and vast. I learn it every day, learn it through pain that I am grateful for: patience is everything!’

Letters to a Young Poet, Viareggio, near Pisa (Italy), April 23, 1903

For Rodin, the language of art is the human body. ‘Man’s naked form belongs to no particular moment in history; it is eternal, and can be looked upon with joy by the people of all ages.’

But his advice to Rilke was mysteriously different: Regardez les animaux. Look at the animals.

Rilke did as he was told. He began making regular visits to the Ménagerie at the Jardin des Plantes. Here, in quiet communion with the zoo animals he found himself learning a way to leave his own skin and enter the skin of another. The discovery came as a shock.

With patience, like winding in a golden string, he was able to arrive at the faculty that is the Holy Grail of poets. William Blake called it ‘Vision’: ‘You have the same faculty as I,’ Blake told an artist friend, ‘only you do not trust or cultivate it. You can see what I do, if you choose. You have only to work up Imagination to the state of Vision, and the thing is done.’

Rilke’s name for this gift was einsehen, ‘inseeing’. To ‘insee’ meant to lose yourself in the undivided otherness of the not-you. Its extremity of empathy melted all boundaries, revealing a world more real than anything Rilke had known. Einsehen allowed him to take poetic receptivity out into the open air, the way Vincent van Gogh carried a canvas, paintbox and an easel.

Sometime during the cold rainy days of November, Rilke spent nine unbroken hours fervently watching a panther pace his cage at the Jardin des Plantes:

His vision, from the passing of the bars, has grown so tired, it can’t hold any more. He feels as if there are a thousand bars and behind the thousand bars, no world. The soft pace of supple, strong steps, revolving in so small a space, is like a dance of strength around a centre where a great will stands paralysed. Only sometimes the curtain of the pupil lifts soundlessly —. Then a picture goes in, tunnels through the rigid stillness of the limbs, enters the heart — and ceases to be.

It’s ironic that Rilke came by his insights into the human condition by communing with animals. Animals—not ones in zoos—live lives that are peculiar to them, individual, full and unconstrained. Put a panther behind bars and it will never stop pacing. Its panther-nature won’t let it. We admire the panther. No matter how paralysed its will, it cannot, as a panther, surrender autonomy over its being. But human life is quite different. The Eighth Duino Elegy tells the blunt, immutable truth:

With all its eyes, the creature world looks out into the Open. It’s only our eyes that are the other way round, like traps laid in front of the exit. We only know what's really out there from the animal perspective; for we take each child very young, turn it round, and force it to look backwards, so that it sees objects, never the Open, never what is so deep in the animal’s face. Free from death. We alone see that; the free animal has its demise always behind it, and God in front, and when it moves, it moves within eternity, as a fountain overflows.

A panther, caged or wild, lives wholeheartedly the life allotted it—unique and individual. There is nothing unique or individual about humans. We don’t even pace our cage. We’re mostly unaware there is a cage. How can it be that panthers are true to themselves, proper individuals, while humans are not? Because what defines individuality is death. If you are unable to die, you are unable to live. The ability to stand alone as a true individual, like a flower in the wind, is the same as the ability to die. Even an imprisoned panther retains that solitary grace. We know it, and admire it—because we don’t have it. Life and death flow inseparably in the panther’s stride. But death is the thing the human species can’t accept. Therefore the panther moves in eternity while we move in time. Time is our prison. And we face a life sentence.

Freud supposed that sex was the primary human repression. Perhaps Lou von Salomé agreed. But Rilke knew the problem was far deeper and more tragic. If we can’t accept the reality of death, we’re forced to reject life in the only form we can receive it. That means our primary repression is the human body itself, with all of its natural spontaneous sensorium, its wonder of presence, its joys and longings, the seat of our being, the paradise we inherited in childhood, the paradise we never forget, and the paradise we are forced to forsake. What should be inalienable gets stolen away. What should be wondrous living corporeal threads weaving every consciousness seamlessly into the fabric of existence gets torn, divided and experienced as dead. William Blake had come to the same irremediable diagnosis as Rilke: ‘For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern.’

‘Inseeing’ starts the journey to rediscover what repression steals: consciousness in search of lost incarnation, in search of the original body—not the outward body as an object experienced apart, but the one Blake calls ‘not distinct from the soul’. To restore us to ourselves and make us whole—this was Rilke’s task, so too Blake’s: ‘Art can never exist without Naked Beauty displayed.’ Naked Beauty incorporates death into life, refuses to put panthers or tigers in a cage. Naked Beauty has no ‘unlived lines’. Naked Beauty, says Rilke, is a ‘carefree letting go . . . not caution, but a wise blindness’:

‘Not the acquisition of silent, slowly growing possessions, but a constant squandering of perishable values. This way of being has something naive and involuntary about it, and resembles that time of the unconscious, best characterised by joyful trust: childhood. No thing is more important than another thing in the hands of a child. She plays with a golden brooch or a white meadow flower. Growing tired, she’ll drop them both carelessly and forget how both shone equally brilliantly in the light of her joy. She has no fear of loss. For her the world is still a beautiful shell in which nothing is lost. That’s why children are so rich.’

On that freezing January morning, Rainer Rilke hurried back inside the warmth of Duino Castle. Immediately, before anything, he dealt with the matter of the business letter.

Only then did he begin to write:

Who, if I cried, would hear me among the angelic orders? And even if one of them suddenly pressed me against his heart,I should fade in the strength of his stronger existence. For Beauty's nothing but beginning of Terror we're still just able to bear, and the reason we adore it so is because it serenely disdains to destroy us.

The voice crying in the wind over Duino Castle was in no way otherworldly—at least, Rilke didn’t believe so. Nor were Blake’s visions. Both poets dedicated their lives to an expansion of ordinary, simple, everyday awareness. Anyone can experience the same. We only need to let ourselves. But we choose not to. Why? We know why . . . because ‘stolen joys are sweet, & bread eaten in secret pleasant.’