Imagine what the newly dead must see.

So long spent looking down on dusty surfaces—

at last, to look up:

through bright-veined leaves,

velvet undersides of petals,

through all the eyelids no longer yours.

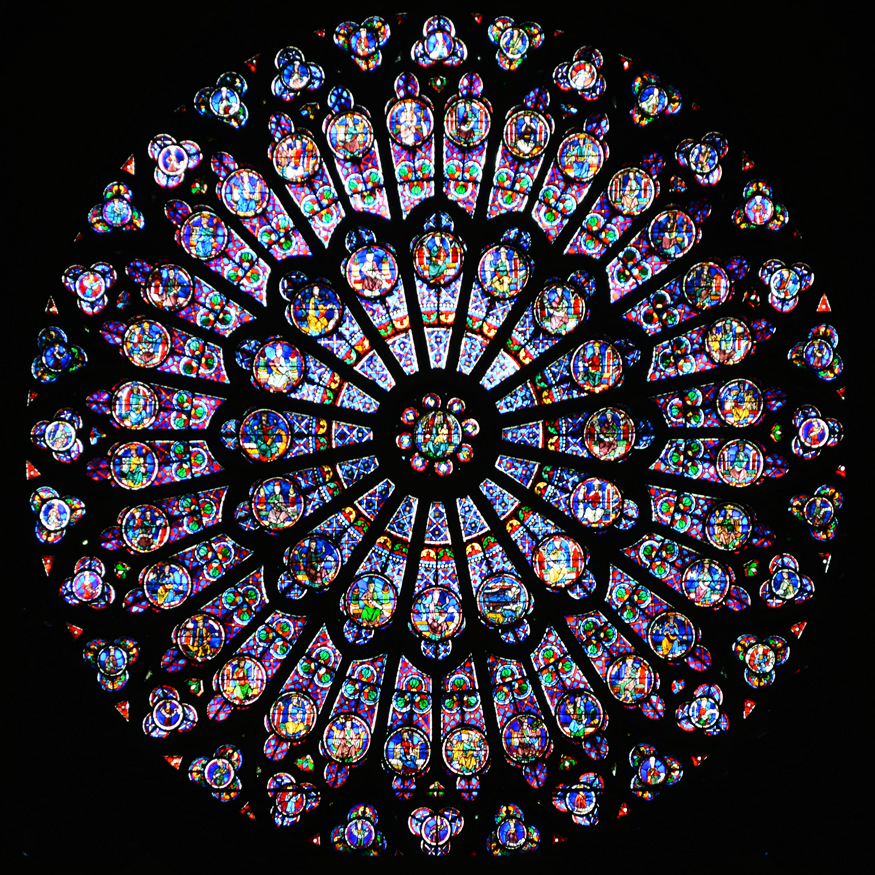

Imagine looking out through the stained glass instead of in,

the purple flood of the rose-window,

the far-off mountain from the fruitful valley.

The first steps with those new eyes

must feel like soles of new feet,

like iridescent toes scrunching silk in a mother’s lap.

The soaring pink pillars of the trees

are now just pure, unclimbable beauty—

as if you were stretched at a lover’s feet

and your eyes fingertips, gazing:

knees, thighs, flank and hip,

the curving belly, gentle pivot of the haloed head—

the halo around the living that only the dead can see.

Full of the strangeness of being

with no desire to be,

the dead still dress in thoughts,

still dress up in dreams,

but now from the infinitely open side,

the side from which death peels off life’s glove

turning existence right-way-round again.

How many necks, Michelangelo,

have twisted in your name?

It’s uncanny, even cruel, to insist the living look into heaven.

Children do it easily, of course,

before the struggle to be tall,

or William Blake chuckling with the archangel Gabriel.

‘Silenzio! Silenzio!’

The Sistine forgives the question

whose feet are trampling away its floor—

the question Adam on the ceiling asks of God:

‘Why—when I lack nothing?’

The dead sprawl and stretch their eternal limbs

and thrust their blissful roots

deeper and deeper into transience.

Adrian Bell