FROM a remote beach on the western shore of the Greek island of Spetses a path leads north around a rocky headland. To the left stretches the wide Argolic Gulf, a smooth sheet of blue in early June. Dry yellow grass, prickly pears, spiky purple-flowered thistles and a mosaic of pebbles cover the surrounding hills to the right, and high up you can glimpse the silver tops of some olive trees. The ground scorches the feet, and sharp-edged little thorny seeds sneak inside sandals. No breeze stirs. The air is very still, tangy, citrusy, hot to breathe, thick with odour of myrtle and broom.

Then the path takes a sudden twist and makes its way down towards the sea. Like much of Spetses, the rocks we descend through are conglomerate, small cobbles and gravels glued tightly together. The rocks are hot and squintingly bright in the sun. Among them we come across a strange little entranceway, a hidden portal, unremarkable and barely noticeable, little more than a crevice.

The lazy sea draws breath, and from the cleft comes a funnel of coolness that invites a closer look: a tight fit, but possible to climb down inside, away from the fierce heat and surface glare. Sunlit steps give way to satiny, flesh-like, hand-hewn limestone ones, leading to a dark interior world.

Down here, an extempore hand has burnished all sharp surfaces to an ice-like, gem-like finish. The air is cold, primaeval, sweet and briny. A shiver runs over your skin as you pass into the shadow away from the warm sun. Perhaps easiest to sit one by one on the slippery, skin-upholstered steps. Leftwards is a grotto of purest blue. Little waves lap lovingly against the stone couches lining the interior shore. The low ceiling shines like wiped tears from blue eyes, and invites an attitude of reverence. Across a Gollum-like lake there stretches a narrow sandy beach, not unlike the one in the world outside, but a beach that’s permanently moonlit, or in receipt of some otherworldly luminescence that lights the sculptures and architectures built there, dwellings, houses, a miniature city displayed under a golden proscenium at the cave’s rear.

This hardly-known and mysterious place is called the Cave of Bekiris. We’re starting our journey here because, by some quirk of chance, the cave serves aptly as a metaphor for the story that author John Fowles imagined taking place at the house on the headland right above where we are. It serves so well in fact, it’s hard to believe that Fowles himself didn’t visit and swim here. The house in the story belongs to a man named Conchis. We will call it the Magus House.

‘It was a Sunday in late May, blue as a bird’s wing. I climbed up the goat-paths to the island’s ridge-back, from where the green froth of the pine-tops rolled two miles down to the coast. The sea stretched like a silk carpet across to the shadowy wall of mountains on the mainland to the west, a wall that reverberated away south, fifty or sixty miles to the horizon, under the vast bell of the empyrean. It was an azure world, stupendously pure, and as always when I stood on the central ridge of the island and saw it before me, I forgot most of my troubles. I walked along the central ridge, westwards, between the two vast views north and south. Lizards flashed up the pine-trunks like living emerald necklaces. There was thyme and rosemary, and other herbs; bushes with flowers like dandelions dipped in sky, a wild, lambent blue.’ (The Magus, Chapter 10)

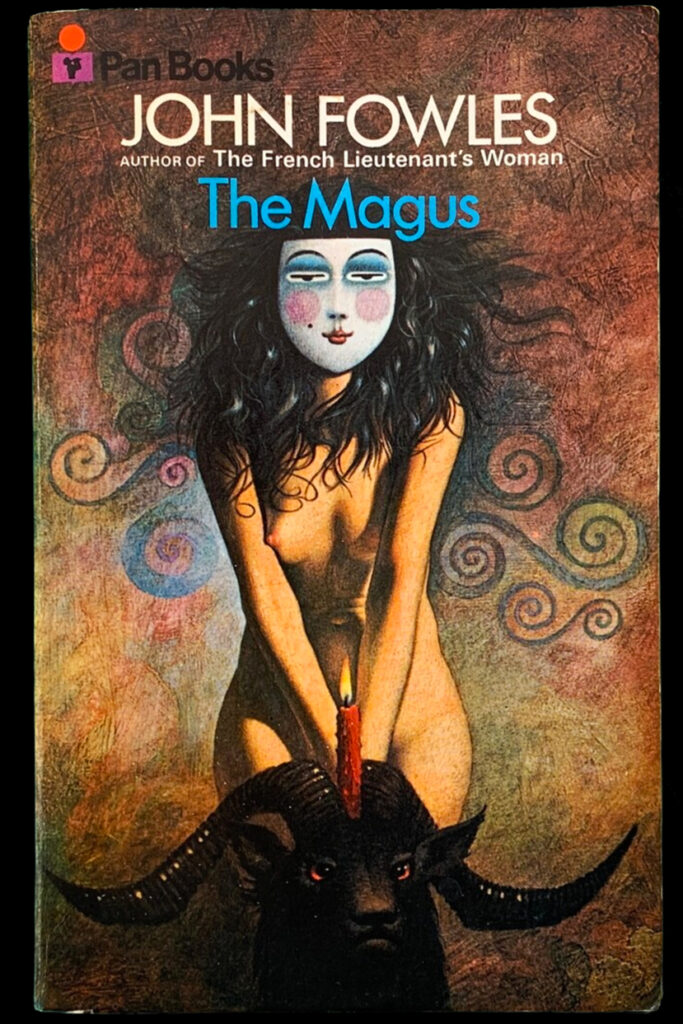

Much of John Fowles’ 1965 novel The Magus is set on an island in Greece he calls Phraxos, lying ‘eight dazzling hours in a small steamer south of Athens, about six miles off the mainland of the Peloponnesus and in the centre of a landscape as memorable as itself: to the north and west, a great fixed arm of mountains, in whose crook the island stood; to the east a distant gently peaked archipelago; to the south the soft blue desert of the Aegean stretching away to Crete. Phraxos was beautiful. There was no other adjective; it was not just pretty, picturesque, charming—it was simply and effortlessly beautiful. It took my breath away when I first saw it, floating under Venus like a majestic black whale in an amethyst evening sea, and it still takes my breath away when I shut my eyes now and remember it. Its beauty was rare even in the Aegean, because its hills were covered with pine trees, Mediterranean pines as light as greenfinch feathers. Nine-tenths of the island was uninhabited and uncultivated: nothing but pines, coves, silence, sea.’

The inspiration for Phraxos was Spetses, west of Hydra. Nowadays, both these islands, plus Dokos between them, appeal to the traveller because they allow no cars. John Fowles came to Spetses at the end of 1951, aged 25, to work as an English teacher at the Anargyrios and Korgialenios School. He stayed until 1953, meeting his future wife, Elizabeth—the model for the character Alison in The Magus—on Spetses. Much of his time he spent exploring the island, ‘with no company but my own freedom.’

On his very first walk to the high central ridge, John records feeling a ‘supreme awareness of existence, an all-embracing euphoria.’ He had the sense of ‘standing on the world, the world below me. I was suspended in bright air, timeless, motionless. I felt incomprehensibly excited, as if I were experiencing something infinitely rare. Perhaps ancient Greece was only the effect of a landscape and a light on a sensitive people.’ This experience, dated January 8, 1952, the author pinpointed as the ‘genesis of The Magus‘.

In coming months he would get away from the school as often as he could and wander alone for miles across the island. He received flashes ‘of vivid perception of the marvellous, the poetic—a tissue of the legendary, the enchanted forest, the spirits of places, nymphs in groves—partly French and medieval, partly Greek and classical, partly my own dream-world.’ He felt haunting presences filling the bright noonday silence. He heard ‘rushing when there is no wind’ and had the ‘momentary impression of a chase, a swift passage of—I don’t know what—bare feet, a shadow in the shade, a stir in the air, lost before I could turn . . . always in brilliant sunshine. . . never frightening.’ There seemed something profoundly meaningful in the ordinary things of the island: the bells of sheep, the thrumming tzitzikas (cicadas) and sad songs of the women. He began keeping nature logs from his walks, recording 86 different birds and 87 kinds of flower. He marvelled to find many orchids, including spider orchids and the tiny human-faced bee orchid.

In late November 1952, John went for a swim alone at the little beach called Agia Paraskevi, ‘the most lovely and most lonely bay in the Mediterranean. A wide beach with a specious pine-grove behind, a little chapel—and absolute peace. In its arms and beyond, the sea and the distant mountains of the Peloponnesus.’ Suddenly another man appeared ‘in shorts and a green shirt, brown-faced, freckled, with pleasant, amiable eyes, an old scout master, one would have said . . . the famous Mr Botassi, who owns the nearby villa Jasmine. He asked me up for coffee after my swim and faun-like disappeared.’

John accepted the invitation. On his way to Botassi’s villa he heard the sound of a harmonium playing, ‘the most incongruous sound imaginable in such a divine landscape.’

The ‘strange little man, childish, charming, full of vitality and enthusiasm; attractively vain, warm and hospitable’ showed Fowles around as if he were ‘a prospective buyer.’ Botassi had planned and built the house himself. It had many round arches, ‘the most wonderful situation in the world, poised as it was on a bluff between two beautiful coves, with the pines plunging into the sea below, the whole Parnon range opposite and the sunny wooded hills of Spetsai behind. One could not dream of a more perfect site—a sublime blend of wood, sea, sun, wind and mountain.’ Botassi took John into ‘a comfortable salon, left me to stare at his pictures, his harmonium—he told me he had sung in opera professionally—to read his guestbook.’ Later they went out on the terrace, and heard a girl singing in the valley, ‘her voice wild, untrammelled, singing some Turkish song which drifted up to us in snatches, without reality. Then we saw a little boy running up a path to the house. “A telegram,” Botassi said. As unexpected as Hermes.’

Petros Botassis’ extraordinary villa was to become the house of the Magus. Equally, Botassis himself would serve as inspiration for the character of the enigmatic Magus, Maurice Conchis: ‘He had a bizarre family resemblance to Picasso; saurian as well as simian, decades of living in the sun, the quintessential Mediterranean man, who had discarded everything that lay between him and his vitality.’

The book proved difficult to write for Fowles, going through fifteen years’ worth of drafts and reworking before its eventual publication. Even then, he revised the book once more for a reissue in 1977.

The story, told first person by the main character Nicholas Urfe, an alter-ego for John Fowles, is complex and full of twists. ‘Urfe’ was how John as a small child said the word ‘earth’. Nicholas, 26, leaves both England and his devoted girlfriend Alison, an Australian air hostess, to teach English at the Lord Byron School on Phraxos. Before he goes, a former teacher at the school cryptically warns him to stay away from the ‘waiting room’. Nicholas arrives in Athens and immediately finds himself in the grip of a strange paradoxical relationship with Greece:

‘When that ultimate Mediterranean light fell on the world around me, I could see it was supremely beautiful; but when it touched me, I felt it was hostile. It seemed to corrode, not cleanse.

It was like being at the beginning of an interrogation under arc-lights; already I could see the table with straps through the open doorway, already my old self began to know that it wouldn’t be able to hold out. It was partly the terror, the stripping-to-essentials, of love; because I fell totally and for ever in love with the Greek landscape from the moment I arrived. But with the love came a contradictory, almost irritating, feeling of impotence and inferiority, as if Greece were a woman so sensually provocative that I must fall physically and desperately in love with her, and at the same time so calmly aristocratic that I should never be able to approach her.’

Once on Phraxos, he soon starts to hate the ‘claustrophobic ambience’ of the school. Long walks across the island help him to escape. He is drawn to the beauty and simplicity of the landscape: ‘It was the world before the machine, almost before man, and what small events happened—the passage of a shrike, the discovery of a new path, a glimpse of a distant caique far below—took on an unaccountable significance, as if they were isolated, framed, magnified by solitude. It was the least eerie, the most unNordic solitude in the world. Fear had never touched the island. If it was haunted, it was by nymphs, not monsters.’

Having always wanted to be a successful poet, Nicholas returns to writing poetry, but soon realises he has no talent:

‘The truth rushed down on me like a burying avalanche. I was not a poet. I felt no consolation in this knowledge, but only a red anger that evolution could allow such sensitivity and such inadequacy to coexist in the same mind. In one ego, my ego, screaming like a hare caught in a gin. Taking all the poems I had ever written, page by slow page, I tore each one into tiny fragments, till my fingers ached.’

Next he discovers two sores, evidence he’s contracted syphilis after visiting a brothel in Athens. Alison tries to contact him, but Nicholas ignores her. Finally, in a deep depression, he takes a borrowed shotgun into the pine forest for an unsuccessful attempt at suicide. ‘All the time I felt I was being watched, that I was not alone, that I was putting on an act for the benefit of someone, that this action could be done only if it was spontaneous, pure—and moral. Because more and more it crept through my mind with the chill spring night that I was trying to commit not a moral action, but a fundamentally aesthetic one; to do something that would end my life sensationally, significantly, consistently, It was a Mercutio death I was looking for, not a real one. A death to be remembered, not the true death of a true suicide, the death obliterate.’

Now at rock bottom, Nicholas travels to Athens to receive treatment for syphilis. He returns to Phraxos. ‘To get through the anxious wait for the secondary stage not to develop, I began quietly to rape the island. I swam and swam, I walked and walked, I went out every day.’ He wanders into the grounds of the Magus House and sees a notice ‘in dull red letters on a white background, SALLE D’ATTENTE.’ Nicholas remembers the warning: ‘Beware of the waiting room.‘

The line: ‘But then the mysteries began,’ introduces Part 2 of the book, ‘mysteries’ doubtless hinting at ancient sacred mysteries, like those of Eleusis. The English word ‘mystery’ derives from Greek mysterion (μυστήριον), meaning a secret rite, a sacrament.

Timothy Leary, the high priest of psychedelia in the 1960s, wrote in The Politics of Ecstasy: ‘Not since I read Joyce’s Ulysses in 1941 have I experienced that special epic-mystery excitement from a book. The Magus raises the basic ontological questions, confronts the ancient, divine mystery and backs away from the riddle with the exact balance of reverence and humor.’ A reader who finds the book pretentious or contrived has missed the point—the point being as sharp and deadly serious as Friedrich Nietzsche’s affirmation of eternal recurrence or Joyce’s ‘History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.’

Restricted to seeing only from Nicholas’ first-person perspective, the reader passes into a bizarre, paranoid world that constantly shifts and disorients. Leary likens The Magus to Ulysses because both books possess an uncanny psychedelic ability to cause heightened awareness of consciousness itself, the organ we look through. John Fowles said he wanted to involve the reader in the creative process of the book. This doesn’t refer simply to interpretation. It means feeling oneself present as witness to the various meta-theatrical stagings and breaks with normal reality that happen throughout the story. By casting us inescapably in the mould of Nicholas’ consciousness, the author brings us slap up against the nature of our own, while simultaneously leading us helpless down the engrossing rabbit hole of yet one more twist in the tale.

The Magus does little to explain itself. For, as Maurice Conchis tells Nicholas, people need ‘the existence of mysteries. Not their solution.’ The puzzle of events and Nicholas’ attempts at solving the puzzle are all part of the same narrative which the reader can’t ever step outside.

Conchis frames the novel’s bizarre events as theatre, blurring the lines between actors and audience, reality and masque. Nicholas faces a series of bewildering encounters, traps and dilemmas. Two girls enter the story, Lily and Rose, apparently twin sisters. Nicholas falls for Lily, despite continuing his relationship with Alison. He’s caught in a web of intellectual and sexual games that force him to confront his vulnerabilities and make him unsure about the identities and allegiances of any of the participants. Finally his own sense of identity begins to crumble. Conchis tells him, ‘Here we are all actors. None of us are as we really are . . . I am an actor too, Nicholas, in this strange new metatheatre. That is why I say things both of us know cannot be true. Why I am permitted to lie. And why I do not want to know everything. I also wish to be surprised.’

Descriptions of the house increase the feeling of vertigo. The interior seems to change and shift like the harlequinades of the story. Though Fowles meticulously describes the layout of rooms, the Magus House seems to morph, maze-like and inconsistent as a dream, at once big and small, light and dark. Its artworks, including paintings by Bonnard and Modigliani, play roles almost like characters in the narrative. Books line the walls:

‘There were two entire sections of medical works, mostly in French, and many—they hardly seemed to go with spiritualism—on psychiatry, and another two of scientific books of all kinds; several shelves of philosophical works, and also a fair number of botanical and ornithological books, mostly in English and German; but the great majority of all the rest were autobiographies and biographies. There must have been thousands of them. They appeared to have been collected without any method: Wordsworth, Mae West, Saint-Simon, geniuses, criminals, saints, nonentities . . . Behind the harpsichord and under the window there was a low glass cabinet which contained two or three classical pieces. There was a rhyton in the form of a human head, a black-figure kylix on one side, a small red-figure amphora on the other. On top of the cabinet were also three objects: a photo, an eighteenth-century clock and a white-enameled snuffbox. I went behind the music stool to look at the Greek pottery. The painting on the flat inner bowl of the kylix gave me a shock. It involved two satyrs and a woman and was very obscene indeed. Nor were the paintings on the amphora of a kind any museum would dare put on display.’

In answer to a letter from an enthusiastic reader, John Fowles wrote: ‘the Magus is trying to suggest to Nicholas that reality, human existence, is infinitely baffling. One gets one explanation—the Christian, the psychological, the scientific . . . but always it gets burnt off like summer mist and a new landscape-explanation appears.’ The animating purpose behind his story Fowles called ‘mystery, pure mystery.’ In the last drafts of the book, he ‘cut down the philosophy’ and kept to straight narrative, eventually publishing the philosophical ideas separately in a very unpopular book, The Aristos.

Our world is ‘interpreted’ (gedeuteten)—always, as Rilke calls it in the First Duino Elegy. Acts of imagination create the objective world. We remain for the most part unaware of this truth. The mind’s collusion in creating our reality is obscured from us—‘unconscious’ was Freud’s term. But our perceptions don’t describe a world outside. They describe ourselves. They describe who we are on the inside. In fact, they are literally identical with who we are. Creating ourselves through the eyes of others makes us act out roles that are fictional, and once identified with these roles, we lose sight of the looker, the witness, the imagination doing the creating. We run from fear of the mind as a solipsistic prison house.

Psychedelic experience suggests that the only escape from the mind is escape into the mind. That means embracing the mind’s nature. The first port of call is to admit the trap. It is the hardest thing to accept that our perceptions are flawed. We live in an interior of cave paintings that we are desperate to confirm as reality. Any challenge to that picture makes us aggressive.

Despite Timothy Leary’s praise for The Magus, John Fowles was always quick to point out that the book was not meant as a work of magic and its inspiration was not drug-induced. ‘For every Rimbaud, there is a world of incomprehensible sots . . . I have never used drugs.’ Equally, John always had a passionate love for nature and wild places. When asked about active measures to restrict the destruction of the world’s natural environment, he replied, ‘I hate such gardening of nature—the labelling, the incorporation of the museum, the city park into what is of its essence wild.’ The solution he thought was simple: ‘reduce the population of the world drastically.’

Where the story of The Magus truly takes place isn’t the island of Phraxos—Spetses—nor the house of the Magus. Its true setting is the mind of Nicholas Urfe. As is the case for nearly all of us, the territory of the mind is as little explored as any Greek island or the interior twilit world of the Cave of Bekiris. Entry to the cave is difficult to spot, a hidden portal, unremarkable and barely noticeable, little more than a crevice, easy to overlook throughout a whole lifetime. From inside however, the cave’s fleshy confines let out into open sky, far off mountains and the deep infinite majesty of the sea, which is, of course, nothing else than that selfsame exterior world we just left—rewitnessed from a vast new perspective.

The success of his books The Collector and The Magus, then later The French Lieutenant’s Woman, allowed John Fowles to become financially independent. In 1968 he and Elizabeth bought Belmont House in Lyme Regis, Dorset, a beautiful Georgian house sitting in an acre of garden. John lived at Belmont until his death in 2005.

Everything The Magus tries to say is summarised in one small poem:

NOT AN OWL

Not an owl on the bough, after all;

but a patch of grey light forcing

through fir. A light-bird,

a bird-light. Retinal phantom.

Or poem to my shortening sight.

Elizabeth Fowles commented: ‘JF wrote this early one morning, sitting at a small table in our bedroom in Belmont, it was so real because owls did sit in the big old pines outside the window, and at night we could hear them.’