THE evening light is tinged with a benevolent cataract of smoke, a kindly soft focus. The cosmos seems half-closing its eyes against the agony of this place, like an impressionist painter who wants to see only beauty not reality.

But Varanasi is all reality. From the ghats along the River Ganges spikes of colourful flame pierce the opaque air, reminding of what the curtain actually hides. From where we are, out on the water, the flames look innocuous, like autumn leaves falling through mist. There is a soft, distant hum. Voices. A clipped mantra. Chanting. The tinkling of cymbals and clang of a bell. A coolness rises from the river, like the detachment that comes at the onset of sleep. But even this far from shore, the pastel pink-blue dusky air is acrid and hard-edged—a contradiction, like everything in India.

Varanasi is proudly, joyously, the city of death. Its antiquity stretches back 2,500 years. It is one of the oldest inhabited places on earth and has received the souls of millions and millions of pilgrims who have journeyed to die in its arms. The funeral pyres on Manikarnika Ghat blaze day-and-night. Pyres built for the wealthy burn aromatic sandalwood and camphor. Poorer folk must settle for wood of the cork tree or the humble versatile neem tree, whose wood India uses for every purpose from making cradles to cleaning teeth. But the very poor, those who can afford only enough cow dung to cremate half a body, must consign what’s left of a loved one directly to the river.

Barges wait, heavy-laden with timber and kindling. Huge stockpiles of logs stand ready ashore. Sunrise to sunrise every day, the ghats—the ancient stone steps leading to the river—witness the cremation of two hundred or more corpses. Cows and stray dogs nose about among the remains. Ashes swirl in the fiery updrafts. The feet of mourners crush underfoot chunks of seeming flame. But they are marigolds, bright little luminosities, twins to the flame, used to wreathe the deceased and attract the impetuous fire-god.

The Ganges at Varanasi curves north in a wide, perfect crescent shape. Looking east across the vast alluvial plain, it’s hard to tell water from land. The two enjoy a fertile symbiosis, older than time, with Mother Ganges serenely swathing all.

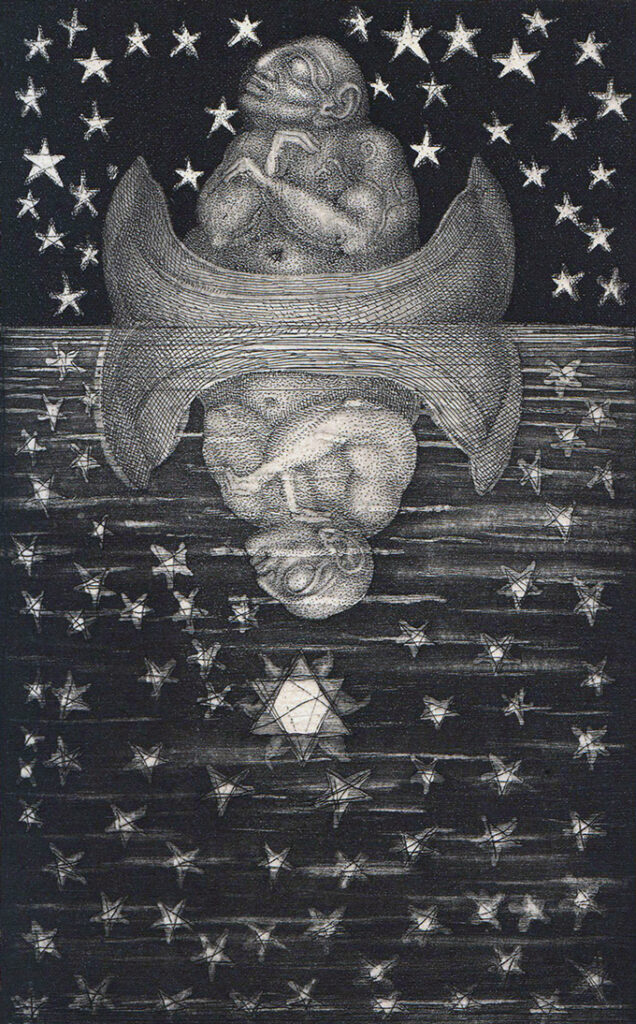

Hindu myth tells how the god Shiva passed the Milky Way through a lock of his hair, distilling the heavenly waters and directing them to earth. Thus he created the river Ganga, his consort, the holy river of immortality, rising in the high Himalayas and flowing to the Bay of Bengal.

Ganges water has a reputation for purity and possessing healing powers. During British Colonial rule in India, the British East India Company carried only Ganges water on board its ships for the three-month journey to England, because it stayed ‘sweet and fresh’. Having swum in the Ganges at Shivpuri, upriver from Rishikesh in the Himalayan foothills, I can vouch that the water is rich in minerals and good for the skin. But mother Ganga is young at Shivpuri. This early in her life, she lifts her skirts of silky, peppermint green and flings herself white and cold over the rapids—a wild, boisterous child compared with the slow, sedentary lady who passes Varanasi.

So we must ask: What makes people gather at the edge of a river whose origins lie in the stars, whose waters are winnowed through the hair of a god, whose beauty and necessity the relentless ferocity of the Indian sun reemphasises every day—why congregate for the strange purpose of burning and disposing of corpses?

Death, and what to do with, it isn’t a problem unique to humans, but one that has beset living things since the inauguration of what we might term ‘sentience’ in primitive life-forms. In fact, sentience itself may have originated as a response to death. Early life-forms evolved the ability to sense necromones, the chemicals that cause the unpleasant smell we associate with decay, the smell that makes us want to run away. We either run away, or seek to dispose of the offending dead thing. A 2015 study by Arnaud Wisman and Ilan Shrira, ‘The smell of death: evidence that putrescine elicits threat management mechanisms’ showed that exposure to putrescine made people more vigilant and triggered thoughts of threat and a need to escape. Even exposure below the threshold of consciousness made the study’s participants aggressive towards people who were not part of their in-group and protective towards people who were.

Is this to do with humanity’s distinctive awareness of death? It seems not, because ants, termites, bees and rats also have ‘corpse management strategies’. Ants drag dead ants out of the nest. Rats bury their dead. Magpies lament over the corpses of other magpies. Cows are terrified to enter slaughterhouses. Elephants will cover a new corpse with foliage, and nudge tenderly the tusks and bones of deceased relatives. After the fatal fall of a chimpanzee from a tree, other members of the chimp’s group were seen howling, beating the ground, throwing rocks and hugging.

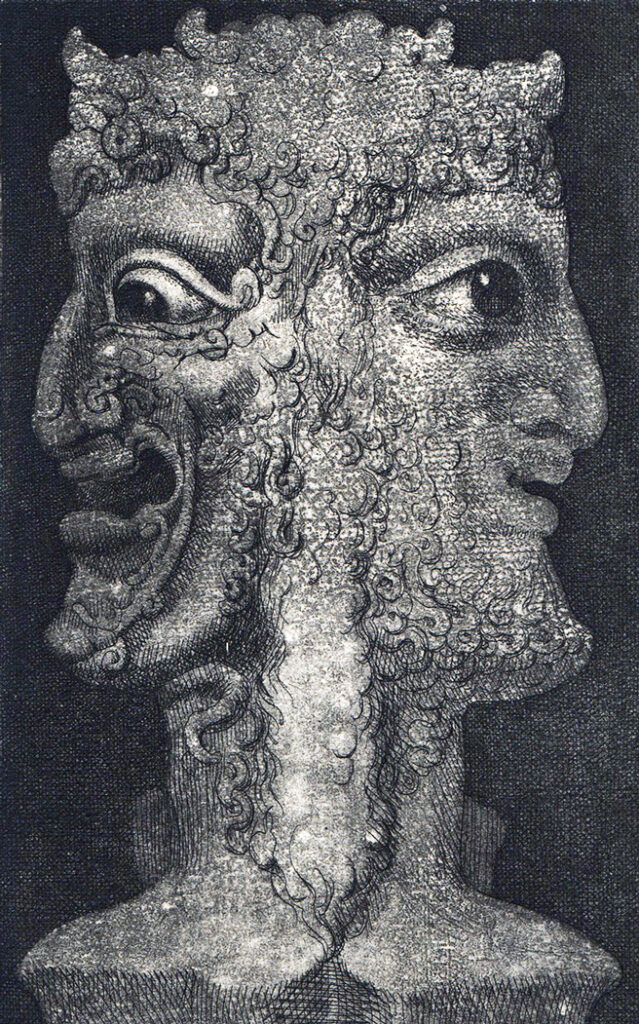

But there is something different about the human preoccupation with death. Do ants know it will happen to them personally? Are cows suspicious that it’s their turn next? Humans know that death is inevitable and permanent. Everyone dies. We know there is personal death, species death and finally the death of the universe. It’s a heavy burden to bear. It might strengthen us, but can also deform, even cripple us.

As a species, our reaction to necromones are highly sophisticated. We’ve turned avoidance of disgust into mass cultural behaviours and lifestyles that keep us out of danger better than any other creature. We’ve devised complex moral codes based on our idiosyncratic idea of what constitutes evil. We pride ourselves on compassion, yet we’re constantly anxious, locked and loaded, ready to aggress against fellows at the drop of a pin. We’ve built the human equivalent of anthills to the point of overrunning the whole earth. And all this we do barely conscious that we’re doing it. Probably no more conscious, one could argue, than ants, rats and magpies. Visitors from another world could be excused for seeing humankind as an infestation on planet Earth.

Death is a specially cruel conundrum for a creature that knows it is a creature, and knows that all creatures must die. Death makes every child a philosopher. The question ‘What is life?’ secretly asks, ‘What is death?’

‘I just feel I’d enjoy it more if I knew what it all meant,’ says Nicholas Urfe in John Fowles’ novel The Magus. ‘My dear Nicholas,’ the magus tells him, ‘man has been saying what you have just said for the last ten thousand years. And the one common feature of all those gods he has said it to is that not one of them has ever returned an answer.’

As babies, we experience the pain of separation when a mother is absent. We discover the law of cause and effect through the magic power of the scream. It teaches us that fantasy can fulfil desire. Wishes can come true. It’s a discovery we can never quite let go of, and one responsible for countless belief systems about causation—scientific, metaphysical or otherwise. Whole worldviews derive from the simple ability to scream. Ask and you shall be given. But what about angry wishes, the ones that arise when we don’t get the satisfaction we crave? Can bad wishes also come true? We can’t tell. All we can do as babies is try to survive.

In this we are helped by a sense of self. No one really knows the origin of the sense of self. Some theories stress social relationship, others environment, others language. Research into early infancy suggests that an ‘I’ feeling predates any conceptual ‘me’. The explicit, objective sense of mineness, me-ness, of myself as something in the world, perishable and susceptible to illness and death, overlays an implicit subjectiveness, what psychologist William James called ‘sciousness’—consciousness that’s not in harness to any feeling of self.

Whatever the case, me-ness is the protective coat we wear to navigate the world:

Mother, don’t you comfort me,

I’m old enough to learn

when there’s only one way left for me

and that’s the way I dare not turn.

Mother, oh my mother,

I am far away at sea

in a ship they say is unsinkable

built specially for me.

Self and the spectre of death come into existence together. They’re polarities, like yin and yang, like two sides of a coin.

One side of the coin is blank—a shapeless, featureless nothing. The obverse side we painstakingly stamp with an image. Creating the self is an arduous process. It’s a work of art, meant to give the coin value and meaning.

But truth be told, money has no value. Its value is symbolic. Only social relation gives money value, and the same is true for the self. Self and its reverse, the ever-present spectre of death, are made of the same stuff. They arise as reactions to one another. Both are inherently empty. One face of the coin is blank, the other covered in magic marks and scratches. The nature of identity, of the self—personhood—is as peculiar as the choice of items that different cultures have used for money: shells, bottle tops, stones, bones, cheese, feathers, salt and teeth. Children use flowers and leaves. All of these can be found adorning dead bodies. All are found in the Ganges river.

Children encounter death gradually. Because it seldom gets mentioned, we have to chance upon it. At first the discovery leaves us in despair. We fear being alone in the dark, monsters under the bed, worms, snails, spiders. We suffer night terrors. We throw tantrums, trying to gain control—control over something—anything—however small. We develop superstitious ways to stay safe:

Whenever I walk in a London street,

I’m ever so careful to watch my feet;

And I keep in the squares,

And the masses of bears,

Who wait at the corners all ready to eat

The sillies who tread on the lines of the street,

Go back to their lairs,

And I say to them, “Bears,

Just look how I’m walking in all the squares!”

‘Lines And Squares’ by A A Milne

Children are said to indulge in ‘magical thinking’. But all thinking is magical. One flash of experience outside of thinking is enough to convince of that. We live in the grip of a magic spell. We buy into the deception because it represents a way to put death in its place. Make it manageable. Bite-size pieces. We learn to live seemingly deathless lives, all the while in death’s shadow. If we start to have doubts about the spell’s potency, other people quickly rush to renew our faith. Language becomes a mantra: reassurance for the living and deliverance for the dead. Eternity smuggled inside time. Mortality posing as immortal.

A long historical process of memorialisation, of rite, ritual and taboo— human history itself in fact—has managed to put death to flight. Yet the question remains: what to do with the corpses? And there are still so many of them. Throughout time, humans have had to dispose of over 100 billion: fathers, mothers, sons and daughters—every one the bearer of a self, every self persuaded that life goes on forever. If not on earth, then somewhere else.

The importance of Varanasi is as a portal, a gateway to one such ‘somewhere else’. Serving that function makes the city at once dreadful and beautiful. It has all the strange ambivalence, endangerment and exhilaration of a threshold, a passage between worlds.

We said that Varanasi is all reality. But it is more than that. Some rare places on earth can make us feel derealised. They are like war zones. Varanasi stands at the confluence between the river of stars and the river of silt and ashes.

As an antidote to the life we think we live, bound in the perceptual chains of the self, Varanasi shows us the harrowing vision of swollen, blue-black death. ‘This body of mine also,’ says the Pali Canon, ‘has this nature, has this destiny, cannot escape it.’ Poverty and mutilating affliction disfigure the city’s blackened streets. The air chokes with the smoke from cooking plates, cremation pyres and cannabis. Mother Ganges washes the bodies of the living and anoints the bodies of the dead.

But another reality saturates life at Varanasi: Sat Chit Ananda—Being Awareness Bliss, the universal ground of being. Varanasi is the place where the dancing god Shiva once manifested before the gods Brahman and Vishnu as an infinite column of light, neither end of which the other two gods could find.

Shiva dances the endless cycle of becoming and passing away, and Varanasi is Shiva’s dancing body. The god simply plays like a child. It is the play of continual, spontaneous appearance in consciousness.

The universe is the arabesque of Shiva’s eternal dance. Creation and destruction for sheer joy. The scrawling signature of play for play’s sake. Life is symbol. Death is symbol. The water of the Ganges that the bathers bathe in is symbolic water. Clean or unclean, nobody cares. It is holy water, the water of eternal play, and the river accepts without distinction the bodies of the living and the dead, cleansed for passage to paradise. Nirvana. The burning ghats offer Moksha—liberation from the unending cycle of death and rebirth. Shiva Nataraja’s ghats are gardens of living flame. The marigolds aren’t flames. The flames are marigolds. The bright folds of saris spread to dry on the dusty steps are divine revelations of pure colour. The living energies of the monkeys chase their tails over hefty stacks of wood whose nature is smoke. The singed wall of the ancient temple works well as the wicket for a game of cricket. Varanasi is the Indian equivalent of William Blake’s ‘spiritual Four-fold London eternal’:

My Streets are my Ideas of Imagination.

My Houses are Thoughts: my Inhabitants; Affections,

The children of my thoughts, walking within my blood-vessels.

Most human habitations want to ostracise death. But in Varanasi daily life is lived among the dead. Varanasi celebrates death. Photos taken a hundred years ago show the same serene water, the same smoking fires, the same bathers squatting on the ghats, the same mourners, the same wandering incurious cows. It’s like looking into a painting you’ve known since childhood and suddenly finding yourself pictured in it. Nothing has changed. You were there all along, just never noticed.

Shiva dances. Oblivious. Indifferent to happiness or suffering. Flames encompass his dance. The weight of his right foot tramples the little misshapen dwarf of the self, the creature we think we are. But Shiva points to his other foot, the raised left foot: Moksha. The way out. The way we dare not turn. Flames that are flowers. Rivers that we can’t step in twice. The thing we actually are and always have been. The thing that frightens us most, and the thing humanity must finally reckon with if the species is to survive. It’s a truth that Beatle George Harrison, whose ashes were scattered by his widow and son in the Ganges at Varanasi in 2001, put very succinctly:

Nothing in this life that I’ve been trying

Can equal or surpass the art of dying.