COBBLED streets, stone-spanned alleys between crumbly bleached walls. Fluted edge to a shadow cleaving a wall. It is cool blue-grey in one half, blinding white in the other. Shadow and sun. Yin and yang.

Kindly plane and chestnut trees shade the lunchtime tables in the squares. Flash of a high-up windowpane among ivy-festooned stones. Small pretty shops entice you under their red umbrellas. Cobalt blue enamel numbers and street names. Oleanders, dusty pink in pots. Knobbly spire of Saint-Martin Collegiate Church spearing up solid as a cypress against the sky.

We’re in the old town of Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. Here, in deep midwinter 1503, the prophet Nostradamus was born. But now it’s early afternoon in May. Baking summer heat makes your legs hurry for shade. No breath of wind. Pigeons flap down to drink at the bubbling dolphin fountain in Place Jules Pelissier. We make our way south— toward Avenue Vincent van Gogh.

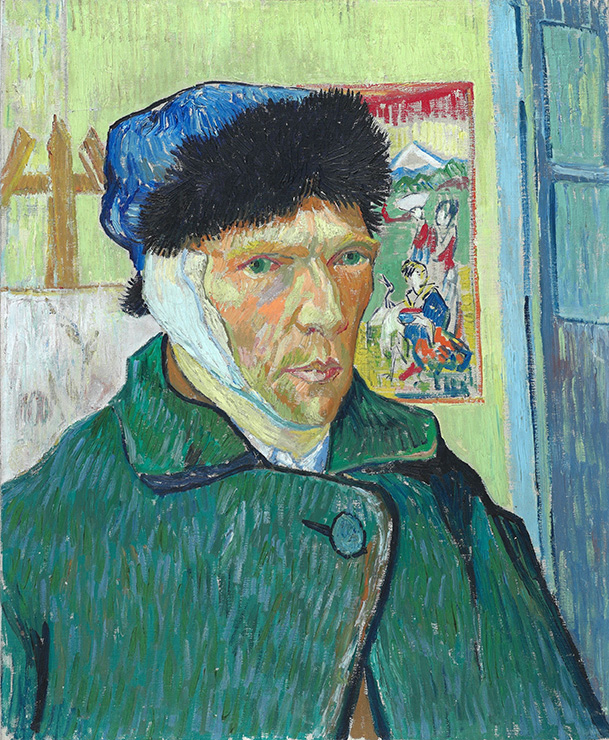

Vincent came to Saint-Rémy to convalesce and recover from what he called ‘my mental or nervous fever, or madness’. Two days before Christmas 1888, he had cut off his left ear. Not just part of his ear—not just the earlobe—but his whole ear.

He had been living in the nearby town of Arles. His friend, the artist Paul Gauguin, had come to live with him. The two quarrelled. Things turned violent. Vincent’s ear got severed and afterward he gave it to a 17-year-old girl who worked as a maid at the local brothel and waitress in the cafe. She fainted.

Disease clings to a man the way ivy clings to an oak. Vincent consoled himself with such thoughts through the early months of 1889. ‘Each day I take the medicine that the incomparable Dickens prescribes against suicide. It consists of a glass of wine, a piece of bread and cheese and a pipe of tobacco.’

He came out of hospital in February. But the mayor of Arles ordered him locked up for another month. The townspeople, who called Vincent le fou roux, ‘the red headed fool’, petitioned for his house, the ‘Yellow House’, to be closed. While he was away from home, damp from flood waters damaged quite a few paintings. By the beginning of May, Vincent wrote to his sister, ‘I have had four major attacks, during which I had no idea what I said, what I wanted or what I did.’ He agreed to go for treatment at Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in nearby Saint-Rémy.

In company with his caregiver, Frédéric Salles, Vincent left Arles by the 8.51 train on Wednesday, May 8th, 1889. Later that day their carriage rumbled up from the train station in Saint-Rémy, along the dead straight dusty road toward the St Paul asylum gates. The road is now called Avenue Vincent van Gogh. Our visit to Saint-Rémy is on May 10th. These days, markers on the ground alert you to many places depicted in Vincent’s works.

By the bridge over the Canal des Alpines, a bleached monument with a cross on top, dated 1877, and a dark green cypress, stand chatting together at the roadside. As if waiting to cross. The ruined human memorial beside the lively, buxom tree. Knight and his beloved lady. ‘The cypresses,’ Vincent wrote from Saint-Rémy to Theo, his brother, ‘continue to occupy my thoughts . . . They have a beauty of line and proportion like that of an Egyptian obelisk. And the quality of the green is so distinguished.’

In the distance swell up the bumps and humps of the gentle Alpilles. Female undulations, as perfect a line as the breast and flank of Goya’s Naked Maja. Soft mountains, reclining in the forks of the almond trees, topped with those milky afternoon clouds that Vincent loved to gambol with. Bedsheet ghosts. Rollicking white balloons.

A bend to the left between leaning pines and ahead lie the thick, buff-brown walls and iron gates of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole. The climb levels out. The shade offers relief. We’re drenched in sweat. To our right, a familiar olive grove nestles under the hills. Vincent here beheld, above the swirling landscape, a mother and child levitate on the wind, as if floating in the currents of a warm pool.

The St Paul gates are open. On my last visit, years ago, I was disappointed. Saint-Paul-de-Mausole was closed to the public. These same heavy gates were locked shut, as they likely were when Vincent and Frédéric arrived. One of the two put a hand to the bell pull at the little door in the wall to the side of the main gates, and rang it.

Today the gates are open wide. I’m bursting with excitement. But it’s cash only, and all I have on me is a card. I find myself with no choice but to run the mile back to town to get money. In the boiling sun, I make the distance as fast as I can, then puff back exhausted up the hill.

Once inside the old hospital grounds, to the left, a bronze statue of an emaciated Vincent, cradling sunflowers and his painting things, welcomes visitors. What would he make of all this adulation? He’d say, ‘Sooner admire the tiny, late-blooming periwinkle flowers. They will tell you more than I can.’

From the eleventh century, these walls enclosed a monastery. From the early 17th, they sheltered people deemed mentally ill. Saint-Paul-de-Mausole has always provided refuge—withdrawal from the world.

Its walls, bare, forbidding, bone-coloured outside, on the inside form a backcloth to a lovely garden: trees, climbing roses, irises, peonies, lupines. Not so much in Vincent’s time. Back then, the garden suffered neglect. Vincent wrote to his brother Theo, ‘Thick tree-trunks covered with ivy, the ground also covered with ivy and periwinkle, a stone bench and a bush of roses, blanched in the cold shadow.’

If illness is to a man what ivy is to an oak, ivy had wisely done its best to keep the wall confining the asylum inmates a secret from them. The thoughtfulness of the hardy little plant was not lost on Vincent. He loved the ivy’s bold cloak covering the St Paul gardens. His brush rejoiced in its every sunny green shade and his pen in its sinuous curl.

Vincent got to know his fellow patients, ‘honourable madmen who always wear a hat, spectacles and travelling clothes and carry a cane, almost like at the seaside.’ Some were seriously ill, howling and raving. But the understanding, sympathy and friendship among the patients Vincent found very moving. Living with people affected by madness, his fear of going mad himself decreased.

In his first month at the hospital he painted Irises: ‘I’m struggling with all my energy to master my work, telling myself that if I win this it will be the best lightning conductor for the illness.’

Flowers like bobbing blue bonnets. Flowers wild with excitement:

Take my hand quick and tell me,

What have you in your heart.

Girls at their first dance, gliding across an earthy red ballroom floor. Craning their necks, tumbling in a hurry to see who’s at the door. Leaping, tittering, shining, wet-winged butterflies. And most shining of all, a white flower, poised like a pure white bride, surrounded by a fever pitch of flowers like creatures from Dr Seuss. And without Vincent, there’d be no Dr Seuss.

Nowadays, this painting lives under glass—it’s in the Getty Center, Los Angeles. But it’s glass you barely notice. The flowers tempt our fingers to touch them—a big no no in a gallery. Touching is a privilege reserved for lucky collectors in the privacy of their own homes.

Blue flames of pure delight. Open-mouthed baby birds. Outpour of song from mystical throats. A lively breeze has sparked a flowerfire. Darting blue-green leaves appear from nothing, the way flames ignite from wood. These regal blue-bloods rush to embrace their orange neighbours with all the passion of Rembrandt’s Return of the Prodigal Son.

‘Sometimes I long so much to do landscape, just as one would for a long walk to refresh oneself, and in all of nature, in trees for instance, I see expression and a soul, as it were. A row of pollard willows sometimes resembles a procession of orphan men.

Young wheat can have something ineffably pure and gentle about it that evokes an emotion like that aroused by the expression of a sleeping child, for example.

The grass trodden down at the side of a road looks tired and dusty like the inhabitants of a poor quarter. After it had snowed recently I saw a group of Savoy cabbages that were freezing, and that reminded me of a group of women I had seen early in the morning at a water and fire cellar in their thin skirts and old shawls.’

Socrates, in the Phaedrus, says that life’s greatest blessings flow from madness. He specifies four kinds of madness: prophetic, poetic, cathartic and erotic. He goes on to recount that once there was an ancient race of people—poets, musicians, artists—whose inspiration so intoxicated them that they sang and danced, danced and sang, forgetting to eat or sleep, till finally they collapsed senseless, dying without even noticing. To honour them and their enthusiasm, the Muses turned their souls into cicadas—those little creatures who sing nonstop from birth to death and never need food or sleep their whole lives.

Vincent knew Socrates’ story well. It came into his mind at St Paul. Maybe he felt like a cicada himself. On 6 July, he wrote to his brother and sister: ‘Outside the cicadas are singing fit to burst, a strident cry ten times louder than that of the crickets, and the scorched grass is taking on beautiful tones of old gold . . . the cicadas dear to good old Socrates . . . And here, certainly, they’re still singing old Greek.’

Never think that Vincent’s mind was not still sharp. While at St Paul, he read in English Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure and Henry VIII. He practised his art with zeal. As part of his treatment, he took two hour baths twice a week. He walked in the cool of the monastery cloisters, enjoying the peace and watching the bright clouds roll over the tower.

Vincent’s presence is everywhere at St Paul. From the cloister, we head back into the low Romanesque corridor and then up wide marble steps set in a soap-smooth, cream-coloured stairway leading to the second floor. Here we arrive at the door of Vincent’s bedroom. Yes—if we’re not faint enough already—this is the selfsame room where Vincent spent his time at St Paul—reading, sketching, writing letters, and hearing the howls and moans of fellow inmates. He made the bed in the corner, his hands feeling the scrape of cast iron across the red floor tiles. He smelt the musty smell of these ancient mildewy walls. This is the room where he often struggled to sleep—the room, he told his sister in September, he was unable to leave for two months for ‘lack of courage’, and because ‘the feeling of loneliness takes hold of me in the fields in such a fearsome way that I hesitate to go out.’

Through the barred window of this room, he made sketches and drawings of the ever-changing landscape outside: a field that grew wheat, the wall enclosing it, some olive trees, cypresses, small huts, hills, and the huge Provençal sky.

On one particular morning somewhere in mid-June, Vincent was up, as he frequently was, long before sunrise. Cold, four-in-the-morning air came in the window. He looked through between the bars and saw Venus, the morning star, low on the horizon, extraordinarily big and bright. Further east, almost out of view, a brilliant moon shone. He was forbidden to paint in his bedroom—he had the use of a room downstairs for a studio. But he was allowed to draw. That morning, he grabbed his things and began a sketch that he later described to Theo as ‘a new study of a starry sky’. Later, downstairs in the studio, he would transfer his drawing to canvas. And the canvas would come to be ranked as one of the greatest religious paintings in Western art.

Like standing under the Sistine ceiling, or visiting the tiny cottage in Felpham, Sussex where Blake wrote, ‘And did those feet in ancient time’ . . . here we are in the place where Vincent van Gogh began work on a vision as penetratingly sincere as anything in Michelangelo, Rembrandt or Blake.

The painting now hangs in New York. Perhaps Vincent would have regretted it’s purchase by the Museum of Modern Art. ‘When I see a painting that intrigues me,’ he wrote, ‘I can never help asking myself, “in what house, room, corner of the room, in whose home would it do well, would it be in its rightful place?”‘ The rightful place for his sunflower paintings was in the Yellow House in Arles. He felt a painting was incomplete without being in its proper home, its original surroundings. That was where it would ‘do well’. A painting belongs to an era, a time and a place where it was created. Moreover, ‘In a word, are there souls and interiors of houses that are more important than what has been expressed by painting? I’m inclined to believe so.’

Vincent always wanted to capture the eternal instant in time. That instant is a painting’s true home. Its vision belongs to that moment and that place. Perhaps it belongs to a single consciousness. Art is a nontransferable ticket. That’s a truth we must accept. And yet . . .

Here is something inexplicable. We have every reason to feel sorry for Vincent. Isolated by illness, loneliness and pain, he suffered deep depression. He knew that paintings aren’t the real thing. Whatever they connect us to, the link is tenuous and fleeting. The vision fades as fast as the sheen on wet paint. But for all that, what is it that Vincent’s paintings show—however imperfectly, however briefly—what is it when he sees—truly sees?

Who can pity the artist who painted The Starry Night? This is not a painting designed to please, arouse emotion or disturb. Vincent’s anthropomorphic descriptions of his work—willows as orphans, wheat as sleeping children, cabbages as women in old shawls—are more than emotional translations of nature into human terms. As in Blake, the anthropomorphic serves a much more profound purpose, to point beyond itself at something still more unifying.

In fact, The Starry Night, as Vincent never tires of telling us about all his work, is an attempt at very straightforward representational art. But what is the painting trying to represent? Maybe it’s just a simple signpost, a way to remember. A mnemonic, no more the substance of the transcendent vision that Vincent saw than ‘Every Good Boy Deserves Fruit’ is the substance of music.

What intrigues about The Starry Night isn’t just the painting. It’s that inscrutable, shining something that Vincent’s brush strokes are struggling but failing to catch hold of. He wrote, ‘Just as we take the train to go to Tarascon or Rouen, we take death to go to a star.’ Standing in front of the painting, we get the uncanny sense that we too are in the presence of that something, aloof in all its incomprehensible glory. Perish the thought that such beauty and terror, such heightened intensity of existence, should leap from the frame.

Our immediate, automatic reaction is to close the blinds against the light. Let the moment pass. Let the seething surface of the paint return to being just paint. Ignore the eerie feeling that The Starry Night is in some sense a mirror, showing us ourselves, reminding us of the swirling tidal pool we truly swim in. Put out of mind the thought that its vortex spirals not above the dreaming town of St Remy, but inwards. Its infinity isn’t out among the stars and sky, but inside us. Vincent witnessed this vision not through his bedroom window in the Saint-Paul asylum, but through an irresistibly compelling window into himself. The same dizzying view beckons in all of us. Only take the plunge. On one hand we long to. On the other, we jump back. What is this freedom The Starry Night opens upon? We admire Vincent’s courage. We fear for his sanity. And that, in a nutshell, is the supremacy of his vision and the tragedy of his isolation. ‘I have risked my life for my work, and lost my mind in the process.’